By Prof Christopher Bertram, Professor in Social and Political Philosophy (University of Bristol School of Arts) & Co-Director of the Bristol Institute for Migration and Mobility Studies;

Dr Devyani Prabhat, Lecturer in Law (University of Bristol Law School) and Dr Helena Wray, Associate Professor (University of Exeter Law School).

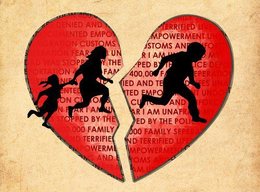

For thousands of British citizens and residents separated from loved ones by the onerous financial requirements in the immigration rules, the headlines after the Supreme Court decision on 22nd February 2017 in the case of MM v SSHD were disappointing.[1]

For thousands of British citizens and residents separated from loved ones by the onerous financial requirements in the immigration rules, the headlines after the Supreme Court decision on 22nd February 2017 in the case of MM v SSHD were disappointing.[1]

The case concerned the entry criteria for a non-EEA national to join their British citizen (or long term resident) spouse or partner (“the sponsor”) in the United Kingdom. These include a requirement that the sponsor has an income of at least £18,600 per annum or substantial savings, with additional sums needed for dependent non-citizen children (“the minimum income requirement” or MIR).

As the press reported, the Supreme Court did not find the MIR incompatible with article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (the right to respect for private and family life) and therefore unlawful. However, hidden behind the government’s reported “victory” is a more complex legal and political picture which offers hope to at least some of those affected.

The Judgment

Judgment has only just been delivered even though the appeal was against decisions adopted in 2014 and 2015, and the case was heard by the Supreme Court in February 2016 but there is no comment on the delay or, indeed, any apology for it. Lady Hale and Lord Carnwath gave a joint judgment with which all the other Justices agreed. The primary challenge was to the level of the MIR. The court found that there was adequate justification for adopting the MIR and that the limit had also been carefully considered and set.

The level had been identified by the Migration Advisory Committee, a committee of academic economists, as the minimum a household needs to avoid eligibility for welfare support. Other expert evidence before the Court challenged some of the conclusions that the government drew from this information, in particular, that requiring this income would lead to significant welfare savings, but this was not even acknowledged in the judgment. To do so, would have required the Court to question the boundaries of policy, a political rather than a legal judgment.

Citizenship rights

The court in MM notes the immigration control objectives of the MIR but the citizenship rights of British partners and family members do not figure at all. Yet, in these cases there is already a citizen or long term resident who is seeking to establish family life in their own country. The MIR acts as a means of long term categorical exclusion of both citizens and their families because the sponsor may never be able to earn enough and the couple may never amass sufficient savings to make good the shortfall. In fact, about 40 per cent of the working-age population earn below this level.[2]

The effect of the MIR on female sponsors is even greater because of the persistent gender pay gap in British society. There are also disproportionate effects because of the lower earnings of some ethnic groups and because of regional wage disparities. It is perhaps surprising that the Court did not pay more attention to the rule’s discriminatory effects; these were dealt with only cursorily. But to do so would again have required a more in-depth investigation of the rationale for requiring that level of income and it seems that the Court was not prepared to do this.

The decision provides a stark example of the weakness of citizenship rights. While the relationship between citizen and state is often presented as a grandiose and lofty one constituted by loyalty, allegiance and service, in practice it is generally a one-way street where the state jealously guards access to resources in fear of potential welfare claims and refuses to grant residence rights to other loved ones. Like a jealous lover, the state is intolerant of any other claimants to a citizen’s affections and is thus ready to see citizens forced to pursue family live elsewhere rather than concede any material benefits to “foreign” families. The onus is on the citizen to prove why they are unable to set up family life outside the UK as that is the preferred option of the British state for those who fail to meet the MIR.

This approach is not unique to the UK however. Elevated income requirements or other similarly onerous criteria are now in place in a number of Western and Northern European states. While the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has not ruled on the compatibility of income requirements with the right to respect for private and family life (art 8 ECHR), its jurisprudence so far does not suggest that it would find a violation unless additional factors such as discrimination were present. In general, citizens’ rights to family life in their own home receive only fairly weak protection in human rights law.

Best-interests analysis

Though the MM judgment avoids discussing citizenship rights, it contains a well-developed analysis of children’s best interests. The judges require the Home Office to adapt the rules and practice to better reflect the best interests of children affected by the MIR in line with ECtHR decisions, most notably that of Jeunesse.[3] The Supreme Court quotes the operative part on children (para. 109) as follows:

Where children are involved, their best interests must be taken into account. … On this particular point, the Court reiterates that there is a broad consensus, including in international law, in support of the idea that in all decisions concerning children, their best interests are of paramount importance. … Whilst alone they cannot be decisive, such interests certainly must be afforded significant weight.

The Supreme Court in the MM case found that while the government acknowledges the importance of a child’s best interests, these have not permeated the framework of the UK family migration regime where neither the Immigration Rules nor the Instructions to decision makers on when to grant an exemption from the MIR adequately reflect the extent of the government’s legal duties. Provision for children in the Immigration Rules only applies in a narrow set of circumstances. Instructions to immigration officers give guidance as to how the interests of children should be recognized by the grant of leave outside the Immigration Rules. These are excessively restrictive.

In essence, exceptional circumstances must exist if a parent is to be admitted outside the Rules:

The key issue is whether there are any factors involving the child in the UK that can only be alleviated by the presence of the applicant in the UK.

Examples of the need for the other parent are support during a major medical procedure, particularly if this is unforeseen or likely to lead to a permanent change in the child’s life, or preventing abandonment where there is no other family member in the UK to care for a child. Clearly, a child’s interests in living in their own country with both parents is not a sufficiently strong consideration to trump the demands of immigration control.

The difficulties are mostly presented as resulting from choices made by the parents:

So the fact that parents have chosen to travel at different times, or maintained separate life-styles in two countries, will not amount to a degree of separation that amounts to exceptional circumstances.

What then might be sufficient? For example, “the impact of natural disaster on the overseas parent’s housing or employment”, making it impossible for the child to “return” to live with him or her, “may count”. Obviously, these Instructions for decision makers make it highly improbable that a child will be able to reside with both parents where the MIR is not met and the numbers of successful applications granted without a human rights appeal are tiny.

The Supreme Court has now required the Home Office to reconsider how the child’s best interests will be given primacy and brought into conformity with the principles highlighted in Jeunesse; particularly of fair balance. In its previous judgments, while it has often criticized policy, sometimes fatally, it has not previously found the Immigration Rules to be unlawful so the significance of the judgment in this respect should not be overlooked. However, fair balance as a step in the proportionality analysis only follows after a stand-alone assessment of the best interests of the child has been carried out.

There are nearly 15,000 children separated from at least one parent because of the current MIR and many of these are British children whose citizenship rights have not so far been acknowledged, as previously required by the Supreme Court.[4] How will the redrafted Rules take into account the absence of a parent on a child’s best interests? In para 100 the Court merely mentions “a broader approach may be required in drawing the ‘fair balance’ required by the Strasbourg court” but this is open to re-interpretation by the Secretary of State in line with her policy objectives and it is to be hoped that the Supreme Court will use its continuing supervisory function in this case to ensure any new approach is sufficiently robust.

In addition, the Court required guidance to be amended to allow other sources of income and assets to be taken into account when considering whether article 8 ECHR requires admission of the partner despite not meeting the MIR. The same concerns apply: A bare acknowledgement that they may count does not provide reassurance that they will receive due recognition.

It is disappointing therefore that the Court did not do more to address the problems faced by separated families, despite acknowledging in para 80 the hardship to them. The Court mentions the problems facing British citizens who have formed relationships while living and working abroad and who now wish to return with their families to the UK. The Court remarks that many of these people formed their relationships before the latest rules were even considered and that their children, most of whom will be British citizens, are severely impacted. Yet, despite this wholehearted empathy for the situation of families, in para. 81 the court observes that hardship is not considered a reason to find any incompatibility or unlawfulness of the rules or Instructions. To do otherwise would have brought the Court into a direct collision with the Government on a key plank of immigration policy and the judgment, read as a whole, suggests a distinct unwillingness to do this.

It is likely that the Supreme Court is weary of adjudicating on the boundaries of article 8 ECHR in immigration law, an issue on which it has ruled more than 15 times in the past ten years. It may be particularly frustrated by the use (as here) of judicial review, which requires the Court to examine the government’s justification for its policies in a highly politicised arena and in abstract, without the ballast provided by a set of concrete facts with which to engage. Yet, judicial reviews are brought because the government persists in refusing applications without adequately considering the human rights aspects.

This forces aggrieved applicants to bring appeals which are then either ceded before the hearing or granted by the First-tier Tribunal (Immigration and Asylum Chamber) or, on further appeal, the Upper Tribunal, – a wasteful, expensive and time-consuming process but one in which each applicant must be ready to engage if they are to obtain a fair decision. Judicial review aims to cut through that by obtaining a general ruling. But, such judicial reviews are very hard to win precisely because the ruling would be a general judgment on the rule not on its application in a particular case and it is difficult for the Court to say that it could never be lawfully applied.

Instead, the MM judgment points to the Upper Tribunal, as the appropriate forum for establishing the contours of a human rights compliant regime which can guide the First-tier Tribunal and where the key is not whether the government can have its policy but whether application of the policy is fair in the particular case. However, it also calls on the government to live up to its responsibilities to make good decisions in the first instance, calling for a “partnership” between the two agencies (Tribunal service and immigration service) to ensure “a system which is to be fair both to the public and to individual applicants” [74]. If the judgment is implemented in good faith – and the Supreme Court will be involved in supervising the redrafted policy and rules at least – there should be a noticeable change in approach. If it is not, the senior judiciary may find that they are not yet rid of their article 8 ECHR workload.

Cost-benefit analysis

While the reasons for the Supreme Court’s reluctance to engage with the government’s justification for its policy are understandable, it does mean that the government’s “price of everything, value of nothing” attitude towards family life and migration has been left mostly intact. The cost-benefit analysis of family life, which has now been popularly labelled “the price tag of love”, is the theme that reverberates throughout the judgment and ultimately emerges victorious.

A typical example can be found in para 94 where, while discussing the situation of a family, the Supreme Court says, “They are unlikely to be a burden on the state, or unable, due to lack of resources, to integrate.” This statement demonstrates the manner in which the Court has adopted the (skewed) vision of the government of the limited or protected nature of the British welfare state.

Why should there be no resources expended for integration of those who are closely connected to the state? Why should such people be relegated to other countries? Despite the high sentiment of the best interests analysis which is coupled with the pragmatic approach towards other available resources, there is an overwhelming agreement between the Court and the Government about the need to exclude “others” who do not belong here irrespective of their genuine relationships and tremendous hardships.

It is in this empathetic yet harsh rejection of the life situations of many British citizens that the MM case has its worst shortcoming. It is particularly disappointing as the government’s case for the MIR based on the potential welfare savings was comprehensively criticized in the evidence, but the Court chose not to engage with this.

The political morality of the UK’s family migration regime

The MM judgment is a legal decision, but it will be relied upon by politicians and commentators seeking to legitimize the current policy. However, the decisions a country takes about migration rights, family rights and the rights of its citizens are ultimately political. They concern what kind of society it wants to be. The justifications offered for the MIR are extremely narrow and focus on two issues: First what is the income level at which a couple will not be a net cost to the state? Second, though this appeared largely as an afterthought, what level of income is needed to allow foreign immigrants to integrate successfully into British society? The invisibility of the evidence on the welfare savings means that the uninformed reader will not appreciate the defects, even on its own terms, of the Government’s argument.

UK family migration and the values of the liberal state

At first glance, the income requirement seems well-rooted in a central liberal value of personal choice and responsibility, according to which citizens may choose whatever plan for life they wish, but must not expect others to subsidize that choice. But applying this private choice model to the family is extremely problematic for several reasons. The first of these is that it will often impose heavy costs on people who cannot reasonably be held responsible for their situation, namely children. Children who are forcibly separated from a parent do not grow up in circumstances that are best for their personal development and a state that brings about such a separation inflicts real harm on its own citizens.

Second, a demanding income requirement represents a failure of reciprocity in circumstances where individuals are denied a fair opportunity to earn the requisite amount. A state which presides over extreme levels of inequality, in which there are massive regional disparities in levels of income and wealth, in which women and members of BME communities typically earn much less than white men and in which many jobs are precarious and ill-paid should not then turn round and further disadvantage those it has already failed. Theresa May PM has famously said that she wants the state to work for everyone, but the acknowledgement that it has not done so undermines the central premise of personal responsibility that the MIR rests upon.

Third, there is an issue of how far we should see some rights as being basic for all citizens and not to be denied lightly to people on grounds of income even when their exercise does impose some costs on others. Rights such as rights to freedom of speech, freedom of association, rights of political participation and access to basic health care are available to people largely independently of their means because we recognize that to deny them these rights would be to deny them goods that are essential to functioning as citizens of a democracy with equal status to others. Many would argue that to prevent citizens from living in the country with the partner of their choice, cutting them off from the goods of family life, is to deny our fellow citizens access to life possibilities that are so very widely shared that it amounts to a disrespect to them as fellow members of our political community. A state that treats its citizens in such a manner cannot reasonably make the demands on them of allegiance and compliance that it does.

Family and spousal migration is only one part of migration policy, and there is the broader issue of what values migration policy should serve generally. In recent political argument in the UK, three sets of voices have been prominent, virtually to the exclusion of all others. First, the proverbial “taxpayer”, the net contributor to government spending. Second, the needs of “business” for skilled and not-so-skilled workers. Third, the “legitimate concerns” of so-called “ordinary people”, constructed as the “white working-class” worried about cultural and demographic change. Largely absent from the discussion have been the autonomy interests that all citizens have in being able to have a valuable set of life-choices available to them, about being able to live, work and settle where they wish, and in being able to make their life with a partner of their choice and maybe start a family. Rather, those interests – that ought to be of central political concern for a liberal society – have been crowded out of the migration debate. This has meant that many of our fellow citizens and their partners have been thwarted in their pursuit of central life goals or forced to pursue those aims through compliance with arcane rules and at the mercy of an unfathomable bureaucracy. If we aspire to the values of a liberal society – as is the official consensus position of all major political parties – our policies ought to reflect them.

_____________

[1] R (on the application of MM (Lebanon) and others) [2017] UKSC 10. On appeals from [2014] EWCA Civ 985, [2015] EWCA Civ 387.

[2] The Migration Observatory The Minimum Income Requirement for Non-EEA Family Members in the UK (27th January 2016).

[3] Jeunesse v The Netherlands (2015) 60 EHRR 789.

[4] See Report commissioned by the Office of the Children’s Commissioner for England, Family Friendly: The Impact on Children of the Family Migration Rules: A Review of the Financial Requirements (2015, Middlesex University and the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants); ZH (Tanzania) v SSHD [2011] UKSC 4.

1. Presumably one of the reasons why the MIR are found to be in accordance with article 8 is that Art 8 does not enable you to carry on family life in the country of your choice.

2. As to the issue of integration is there any proper evidence that only the better off integrate ?

3. The idea in the judgement that a child should not have to live with both parents conflicts with recent government policy on children in care where it has been said that adoption and therefore the care in most cases of two parents – there are also single adopters – is an urgent matter which government policy has said must be speeded up. So some discrimination here between children who have one non-EU parent and children in care both of course not responsible for their situations.

4. In the recent budget it was said that the self-employed earning £16,000 can afford to pay more tax but a that level of income they are not considered to be earning enough to marry a non-EU spouse and not be what former immigration minister

James Brokenshire called a “burden on the taxpayer”.

I’ve read this very interesting piece as a layman and you must forgive the fact that some of the finer legal points have gone over my head. However, i was particularly interested in the discrimination angle which seems to have been largely ignored by the Supreme Court. Notwithstanding the reasons why this disregard for the discriminatory effects of the government’s policy may have occurred, is there a legal process that can and perhaps might be taken by those who feel that they are being discriminated against? Or, is this all likely just to be of academic importance with a paper written here and there and a reply given by academics but nothing concrete happening for those whose lives are affected?

I’m fishing really for a glimmer of hope for my own circumstances. I’m a UK citizen, aged 64. I am a retired teacher and was living on some savings and a teachers’ pension of £8,200 pa following early retirement at 58 ( I did continue with some private tuition work on an ad hoc basis and wrote a couple of books). I then, by chance met an Argentine woman, an English teacher in Argentina, aged 49 and to my surprise, we fell in love. We married after about 18 months and then our nightmare began. I had no idea about the immigration rules and I had told her that we could live ok in the UK, Spanish, her native language, was a shortage subject ( it wasn’t by then,, but I didn’t know) and she could also look at teaching English. We planned to live in Argentina for 2 or 3 years until her son finished school and then we would start life in the UK. I got Argentine residence and that’s what we started to do.

However, the climate in Tucuman, north west Argentina was unbearable for me for 6 months of the year so we have now moved to Spain and will look to do the Surinder Singh route.

My point is, when I get my State Pension in September, I will still be £2, 500pa short of the MIR. I have never had anything near £21,000 savings that would fill that gap, let alone £62,500. Yet here I am, a full work record in teaching and with Citizens’ Advice, never claimed benefits, always paid tax and Ni but we are deemed unfit to grace these shores. I have tried to find an angle to pursue this but cannot, my MP is completely disinterested, my MEPs don’t even respond. There is simply nowhere to go and I know that those with kids are in an even worse position.

I will simply never meet the rules. We will probably fail the Surinder Singh test and so we have the option of living illegally in the UK for the rest of my life. Some reward for my small contribution to the UK over my lifetime.

I’m in a similar position to Kevin, 64 years old and getting pension credit after many years on Incapacity Benefit and ESA in the Support Group. My partner for the past five years is Filipino, she was in the UK for three of those years working while studying as a carer in an old folks home. There is no way a person who only receives the State Pension can possibly meet the MIR, is this not discrimination?

We have bought a house in Bulgaria and it looks like I will be forced to move from the land of my birth, the country I served the army for, where I tallied a 100% payment of National Insurance contributions till today.

The funny thing is while my partner was in the UK she clocked up £18,600 a year on her own and if she was allowed to stay our household would have an income such that we would have been above being eligible for any state benefit.

I urge anyone with the means to challenge MIR on human rights grounds to do so and we should all expose this unjust and discriminatory legislation for the scandal that it is.

I have been in England as a failed asylum seeker for the past 5years. I met my boyfriend who is a pensioner and he is on state pension of £695 and he has a fully paid off house . Iam Zimbabwean and he is English born and bread in Sheffield. I have lived with him for over a year and our relationship is 2years and some months old. We live together and neighbours and his children have written letters of support and we submitted evidence of council tax bill and photos together. We have submitted to the Home office the evidence and we were turned down and told that its not a genuine relationship. My boyfriend is 13 years older than me and we love each other. Iam not sure what the HO means by its not a genuine relationship.

We live together and neighbours and his children have written letters of support and we submitted evidence of council tax bill and photos together.