By Caoimhe Ring, University of Bristol Law School

“As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect.”

― Franz Kafka, The Metamorphosis (Schocken Books 1948, trans. Willa Muir)

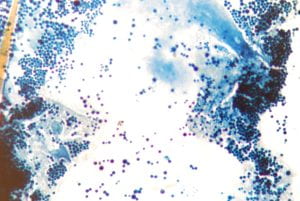

What can Socio-Legal Studies learn from the termite hill? From the microbes in Louis Pasteur’s petri dish? Or the dust on the files of the Conseil d’État? All of it, the late Bruno Latour tells us, are informants carrying clues about the processes which make up what we call society or culture. These things—from pipettes to armchairs, to mice and files—can be considered equally as participants in social action. At this suggestion, many Socio-Legal scholars recoil. The common riposte is that objects do not feel like the typical subjects of our research; the décor does not share the drama with the actors. Even if they are not reducible to such tendencies, Socio-Legal questions carry attendant humanist impulses; a commitment to human dignity and the complexity of the human condition. The constructivist paradigm places a primacy on methods which centre human agency, such as being in the field and on face-to-face methods precisely because we seek to explicate the social dimensions of law. Objects, however, are more than the ‘scenery and stage props for the spate of human action’ (Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life 1956, p.13). Amidst the climate crisis, it has never been timelier to review Latour’s contributions to challenge the Western, capitalist human exceptionalism implicit in the canon of Socio-Legal Studies. (more…)