Prof. Xinyu Wang (China University of Political Science and Law) and He Xiao (a law PhD student at the University of Bristol)

Since October 2020, a “Stop Period Shaming” campaign has been quietly taking place within universities in China. It all started in early 2020, during China’s fight against the COVID-19, with various socially sponsored donations of medical supplies and an extreme shortage of feminine period products. The female doctors and nurses, who made up more than half of the medical team that went to Wuhan, overcame their cycles’ fragility and fought like the male doctors.

Still, the extreme lack of feminine period products made their lives difficult in a closed work environment. This inconvenience initially failed to attract public and official attention because of the widespread belief that feminine period products are in the private sphere. At that time, the Lingshan Charity Foundation in Wuxi, China, initiated the “Sisters Fighting Epidemic Public Welfare Project” to raise funds for female medical staff’s physiological supplies to address the practical difficulties faced by female medical staff on the front lines against the epidemic. Although women’s cycles are universal and regular, individual periods can become irregular and abrupt with emotional ups and downs and increased fatigue. The sudden onset of menstruation often leaves women passive and embarrassed.

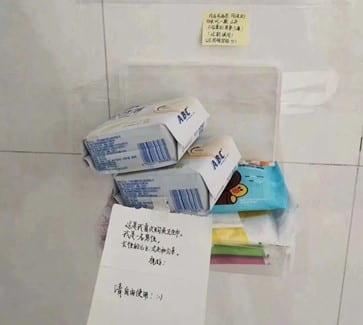

Perhaps based on the resonance of women’s life experiences, on October 14 this year, the project’s founder, Jue Liang, posted again on Weibo about the box with free sanitary pads. A week later, a college girl at East China University of Political Science and Law was inspired by this Weibo post and placed boxes with free sanitary pads outside four bathrooms in the university building. [i] Subsequently, college girls at the China University of Political Science and Law (CUPL) started mutual support. Unusually, CUPL’s motion was supported by a college boy who posted a warm message identifying himself as “a male, son, husband, and father of a female.” His actions quickly drew ridicule from within the male community, implying that the guy was trying to impress the college girls.

Another college boy even launched a confrontational “tissue paper boxes for masturbation” as a sign of equal rights,[ii] Although a boy quickly removed this box with a warning, “Don’t behave like that again.” With the reversal of the story and the various media responses, the action of setting up a “sanitary napkin box” has gradually become a gendered issue.

In China, the “box with free sanitary pads” first appeared in the public eye. In most countries, women’s sanitary pads are not available in the public restrooms of universities, and the suddenness of the menstrual cycle does make life difficult for women. By their nature, the original “sanitary pad boxes” were caring in the light of women’s experiences. However, from the donation of sanitary products by female medical and nursing staff during the epidemic to the launch of the “free sanitary pads boxes” by female students in high schools, it has been within the female community.

The insensitivity of gender experience is often masked by gender neutrality, as Okin argues: “Thus gender-neutral terms frequently obscure the fact that so much of the real experience of ‘persons,’ so long as they live in gender-structured societies, does in fact depend on what sex they are.”[iii] If the “box with free sanitary pads ” evokes only empathy within the female community, then the presence of the college boy of CUPL rewrites the internal caring between women. From his message, it is clear that the young man places acceptance of the female experience within intimacy, which is expressed in gender care. Although this caring is a spontaneous awareness, it at least represents a crucial acknowledgment and support by males for the female experience. The importance of this lies in the gender neutrality of public facilities, as defined by the sanitary products in the restrooms, as a criterion for resource allocation based on male needs in general and male experience in particular, ignoring female experience and female markets. The male student’s presence not only incorporates the gender experience into the ethics of care embodied in intimate relationships, but also promotes awareness of the gender experience through unconscious actions.

Traditional perceptions of gender have been stuck in gender stereotypes for a long time. The appearance of the “tissue paper boxes” for men is actually a sexual association with women’s menstruation, which is one of the gender stereotypes. The emergence of the “tissue paper boxes” for men is an instinctive reaction, but it is also an opportunity to popularize gender knowledge through gender experience, to fully recognize gender differences, and reverse the misconceptions of gender cognition in different levels of physiological material needs. The female cycle is an inevitable part of a woman’s life and requires not only special legal protection but also proper social recognition and acknowledgment so that women’s special needs can be included in the scope of public decision-making. A good example is Scotland, where on November 24, 2020, MSPs voted unanimously to pass the Period Products Free Provision, a bill dedicated to ending period shame, eliminating period poverty, incorporating women’s needs into public decision-making, and securing them through national legislation.[iv]

This campaign is not only against the traditional ignorance of “period shaming” but also against gender stereotypes. It is just that fighting gender ignorance does not require a gender war in the form of gender antagonism. Although male sexual needs are not comparable to the female period, acknowledging and accommodating such individual sexual needs is a form of gender care and need not be hostile. Just as when the “tissue paper boxes” was first introduced, I have also suggested putting up a sweet reminder to ” do as much as you can” instead of removing it. Girls are not ashamed of their period, boys are not ashamed of their sexual needs, and there is no shame in human beings’ various physical characteristics. The human social experience is not single-gender experience, discourse right is not single-gender discourse right, knowledge is not single-gender knowledge, and “the power-knowledge relationship is not a set form of distribution, but a ‘mother of transformation.'”[v]This transformation depends on a common understanding of gender experience, not gender antagonism; biologically based gender knowledge and moral judgment grounded in gender norms are not on the same level, and the paths to gender justice will necessarily be chosen differently.

While a campaign can make feminist rights more visible, gender care is the higher form of gender justice. We “shall analyze each of these types of theory from a feminist perspective-one that treats women, as well as men, as full human beings to whom a theory of social justice must apply.” [vi] The feminist movement can promote the legalization of rights to achieve formal justice, while the widespread dissemination of feminist knowledge can promote gender care and lead to substantive justice.

This blog was written as part of Research on Legal Safeguard System of Chinese Women’s Development Right(19BFX045), funded by National Social Science Fund (China)

[i] Yan Yu. Against ‘Period Shame,’ More Than 20 Universities Launch Mutual Aid Campaign for Sanitary Pads. The Penglai News, Oct.28, 2020.

[ii] Tiffany May, Amy Chang Chien. ‘Stand by Her’: In China, a Movement Hands Out Free Sanitary Pads in Schools. New York Time, November 9, 2020.

[iii] Susan Moller Okin. Justice, Gender, and the Family. Vol. 171. New York: Basic books, 1989, p.11.

[iv] Laurel Wamsley. Scotland Becomes 1st Country To Make Period Products Free. National Public Radio, Nov.25, 2020.

[v] This quotation is based on the Chinese version of Michel Foucault. The History of Sexuality. Shanghai Century Publishing Group, 2018, vol.1, p.64.

[vi] Susan Moller Okin. Justice, Gender, and the Family. Vol. 171. New York: Basic books, 1989, p.23.