By Dr. Paolo Vargiu, Lecturer in Law (University of Leicester)

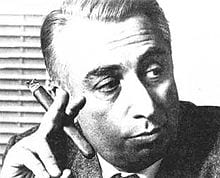

Roland Barthes was never particularly interested in the law. Were he alive today, however, it is hard to imagine that he would be a strong supporter of a regime like investment arbitration – a system which, in spite of its best original intentions, has long been exposed by its critics for the lack of balance in rights and obligations and the abuse of the mechanism to increase the already disproportionate power of multinational corporations vis-à-vis the state where they invest. However, his literary production can nonetheless serve as a model for inquiring on aspects of the investment arbitral regime that remain somehow at the margins of the scholarly critique.

Roland Barthes was never particularly interested in the law. Were he alive today, however, it is hard to imagine that he would be a strong supporter of a regime like investment arbitration – a system which, in spite of its best original intentions, has long been exposed by its critics for the lack of balance in rights and obligations and the abuse of the mechanism to increase the already disproportionate power of multinational corporations vis-à-vis the state where they invest. However, his literary production can nonetheless serve as a model for inquiring on aspects of the investment arbitral regime that remain somehow at the margins of the scholarly critique.

In his essay “Writers, Intellectuals, Teachers” (1971), Barthes theorised an imaginary contract between teachers and students, with specific tasks and expectations brought into the contractual relationship by both parties. Barthes’ teachers are neither mere providers of information nor simply the means used by the school to educate students: instead, they are at once erudite, educators, mentors, instructors and tutors. The term magister may be more appropriate to define Barthes’ teachers for they carry the burden to not only instruct on specific tasks, but also to represent schools of thought, and to act as guides, almost gurus, towards enlightenment, knowledge, and skill. They are vested, in other words, with the duty of developing the community they guide; and, rather than self-conferred, it is a duty given to them by such community.

This can be compared to how the investment legal community looks at arbitrators. It is has been argued that the investment arbitral regime is no longer adequate to settle disputes between investors and states: it dramatically affects development and equality and can represent a significant obstacle to the protection and promotion of human rights, public health and the global environment. Realistically, however, investment arbitration is not going away anytime soon: it is therefore crucial to address the role of arbitrators in the regime, alongside those of investors and state that have been subject to thorough scrutiny by the scholarship. Barthes’ theory of the teacher/student relationship offers a key tool to analyse the relationship between arbitrators and the stakeholders of investment arbitration under a duties-based perspective. Rather than limiting the duties of the arbitrators to the management of the disputes for the parties and the writing of an award that only affects said parties, I argue that arbitrators – as leaders of the field of investment law – should be made accountable for a number of other responsibilities. Arbitrators are to provide, by means of their awards, opinions and scholarship, advancements in the substantive knowledge and the multilateralization of the field; they must consider, when writing an award, that they are drawing the path upon which the future generation of lawyers will be educated; they have a duty to explain, thus sharing, their research and their decision-making methods, and to provide clear, reasoned and sound decisions and opinions that other writers can tap into; and they must approach the questions posed to them rigorously, and that they do so in light of the lines of interpretations (which could be called “schools of thought”, broadening the scope of the expression) established in the case-law. This does not mean that arbitrators must adhere to the established lines of interpretation, or that such established interpretations should not be subject to critique. However, it is fundamental that arbitrators take the existence of settled interpretive methods and reasoning into consideration when deciding their cases, and either consolidate them by using earlier case-law to back up their arguments or contribute to the development of the field by challenging the status quo.

The rationale behind this redefinition of the role of arbitrators lies in the fact that they are not merely passive decision-makers in a determined case: when deciding on a case, arbitrators are in fact active participants contributing to the development and shaping of international investment law. The impact of decisions and awards is not limited to the parties of the dispute in the context of which they are issued, but rather significant for a wide range of other subjects: other states involved in investment relationships with foreign investors, investors that may at any point file a claim before an investment arbitral tribunal, scholars who analyse the investment arbitral case-law and teach the next generation of investment lawyers, NGOs and associations interested in the subject matter of the cases, and the taxpayers of the host states that shall, at some point, bear the costs of investment arbitral disputes in which their home state appears as respondent.

From a purely positivist perspective, one may argue that there is no legal basis to extend the duties of arbitrators beyond the parties to the dispute. However, investment law is factually based on a wide range of bilateral investment treaties and investment protection chapters in free trade agreements – and yet it is treated as a single, homogeneous field due to a multilateral approach that finds its foundations and pillars in arbitrators’ constructions which have weak – if any – legal bases. For instance, there is no hard law stating that tribunals hearing different disputes should interpret different treaties in a consistent matter and the definition of “investment” commonly referred to in arbitral disputes has been construed in a few cases in the 1990s. Furthermore, the actual content of the most common standards of protection have been developed by various arbitrators sitting in a number of different arbitral tribunals. Nevertheless, arbitrators and the stakeholders of investment arbitration treat investment law, and write about it, as if its legal bases were solid and clear. In fairness, if there is a foundation for the whole investment law construction, it is the arbitral case-law – which, in turn, arbitrators and stakeholders consider as expression of a system when it is in fact a collection of awards from independent tribunals dealing with independent disputes. What is the reason, therefore, to approach the question of the arbitrators’ duties from a purely formalistic perspective since the whole regime is based on a very liberal approach to their awards considered collectively? By analysing the role of the arbitrator through a Barthesian lens, the significance of their agency and participation in the process of shaping and (re)developing international investment law is revealed. It is this aspect of international investment law that requires further attention if this discipline is to be properly understood.