By Dr Lorenzo Cotula, Principal Researcher at the International Institute for Environment and Development; Honorary Professor at the University of Strathclyde.

As our demand for material goods drives natural resource extraction, the law reconfigures control over resources to facilitate the production of tradable commodities. Faced with profound social transformations, indigenous and agrarian movements have mobilised human rights to reclaim land, resources and development pathways. This recourse to rights provides distinctive insights on the place of human rights in social justice struggles.

Resource control and international economic law (IEL)

The growing levels and expectations of material consumption in the rich world rest on the large-scale production of commodities for food, energy and raw materials. The correlative expansion and intensification of natural resource extraction has historically involved large-scale mining, petroleum, logging and agribusiness developments, but also more indirect forms of resource control, for example through the integration of small-scale producers into commercial value chains.

As I argued elsewhere, the law underpins this harnessing of natural resources for commodity production. Legal technique converts land and resources into commercial assets, for example through property rights, corporate structures and contractual relations. Recurring features of national legal systems – from states’ extensive resource allocation powers to pro-business law reforms and weak protection of local resource rights – make it easier for businesses to obtain commercial concessions. And international investment treaties can protect investors’ rights and expectations in connection with deals that, while compliant with national law, dispossess local groups.

These interlinked local-to-global arenas problematise the conventional framing of IEL as a field of study – because in commodity relations, the global penetrates the local, and the more difficult issues often lie at the interface between different spheres of national and international regulation.

Reactions from the ground up: the place of human rights

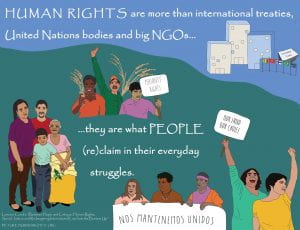

People have experienced transformations in livelihoods, both positive and negative, in their socio-cultural relation with the environment, and in the fabric of societies. But people are not passive “victims”, or “beneficiaries”, of resource commercialisation. Across the globe, citizens have exercised agency to support or contest the deals, renegotiate their terms, or demand alternative development pathways. In spite (or possibly because) of the role the law plays in structuring commodity relations, this advocacy has often engaged with legal concepts and processes. Recourse to human rights has featured prominently, and in a new article I distinguish two interlinked modes.

The first is “reactive”, as activists rely on existing human rights instruments to contest specific instances of dispossession. Examples include indigenous peoples’ mobilising regional human rights institutions to resist resource projects on their ancestral lands, leading to jurisprudential reconfigurations that emphasise the collective, socio-cultural dimensions of the connection between people and territory; and transnational litigation for corporate accountability that harnesses, in subversive terms, openings provided by the geographically and juridically dispersed sites of transnational commodity chains.

The second mode is “constitutive”, in that advocacy seeks a more foundational reconfiguration of human rights themselves. An example is agrarian movements’ struggle for the adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas. The Declaration departs from the liberal human rights canon, placing work at the centre of rights constructs, affirming peasants’ human rights to land and to seeds, and linking human rights to the structures of agricultural production and commercialisation.

Both reactive and constitutive modes go beyond legal arrangements and harness rights language in collective action and discursive practices – from adversarial strategies that contest and challenge, to dialogue-based approaches.

The critique of rights

This recourse to rights coexists with a new surge in critiques questioning human rights’ emancipatory potential – from claimed conceptual commonalities between human rights and prevailing economic organisation; to arguments that human rights fail to address inequality, and mitigate deprivations without challenging the systems those deprivations are a manifestation of.

These diverse critiques identify real issues. Many human rights concepts are historically associated with a juridical tradition that is coextensive with the global economic architecture. Some human rights approaches emphasise the role of the state as a “duty bearer” more than right-holders’ agency, and are overly narrow and legalistic. In interpreting socio-economic rights, international jurisprudence has been reluctant to confront distributive issues. And human rights judgments and instruments have often failed to deliver hoped-for practical results.

But the human rights field is diverse, and concepts are contested and subject to renegotiation. Grassroots activists, international agency staff and due diligence lawyers will advance different practices. Scholars from the global South have long been attentive to this diversity. For example, Issa Shivji reframed human rights as an “ideology of struggle”, while Upendra Baxi distinguished between human rights as a technique of global governance, and as “insurrectionary praxis” that, in giving voice to human suffering, destabilises socio-political ordering.

Rights-claiming as a practice of contestation

In natural resource struggles, many rights strategies – both reactive and constitutive – short-circuit the terms of prevailing debates. While much critique interrogates institutionalised human rights practices in national polities or at the United Nations, indigenous and agrarian movements’ advocacy largely originates outside mainstream human rights organisations and confronts local-to-global governance arrangements. Emphasis on collective rights questions human rights’ supposedly individualistic nature. While some critique has linked human rights to “basic needs”, advocacy is often about recognition, voice and historical redress. And unlike legalistic approaches, these initiatives embed legal action in social processes – so juristic and discursive practices intersect and cross-fertilise, and human rights are both vehicles and outcomes of political action.

Yet, invoking rights provides a channel for social actors not only to seek certain legal or material outcomes, but also to articulate a rupture – cementing social identities, catalysing mobilisation and legitimising counter-hegemonic worldviews. And where activists appropriate rights to sustain mobilisation, action is not restricted to the conceptual perimeters of jurisprudential interpretations. Experiences of indigenous communities occupying the lands they sought restitution of, in the face of state non-compliance with international judgments, exemplify how social actors can shift registers in different times and places, while also using human rights to legitimise conduct that would otherwise contravene domestic law.

At a deeper level, reclaiming the notion of ‘peasants’, asserting the intimate connection between people and land, and seeking to shift public narratives about development paradigms all challenge ingrained prejudices about the ‘backwardness’, or ‘modernity’, of different forms of natural resource use. These prejudices provide the conceptual foundations for the structural discrimination that peasants and indigenous peoples experience in many legal systems.

These dimensions vary in reactive and constitutive modes, and failure to differentiate can create analytical confusion. In pursuing certain practical goals, reactive modes may require tactically accepting positive-law configurations that do not align with social actors’ worldview, and which might in fact indirectly reinforce commodification. Constitutive modes may have more explicit normative connotations and enable more radical departures from prevailing juridical arrangements. This does not mean the social justice demands are themselves more radical, but advocates have greater latitude in articulating those demands in human rights terms.

Between hope and critique

Critique is the engine of change, so it is essential that advocates interrogate their approaches and reorient them accordingly. As critical human rights thinkers and practitioners have noted, the present time requires “a political assessment of both the risks and the possibilities associated with human rights language and institutions”. Existing critiques have exposed human rights’ conceptual and practical limitations.

But rights strategies in natural resource struggles illustrate how, in an evolving kaleidoscope of human rights approaches, alignments with hegemonic discourses can coexist with more radical practices. We need to more fully consider the practices of actors located in geographic, economic and epistemic peripheries, and natural resource struggles provide fertile ground for this exploration.