By Ms Joanna McCunn, Lecturer in Law (University of Bristol Law School).

Contractual interpretation continues to be a controversial topic. In a recent speech, Lord Sumption attacked Lord Hoffmann’s judgment in Investors Compensation Scheme [1998] 1 WLR 896, still the leading case in the area. For Lord Hoffmann, the key question was what a reasonable person would understand the parties to have intended by their contract, even if this was something different to the ordinary meaning of the words they had used. Lord Sumption, however, argued that the courts must give primacy to the meaning of the words.

It is sometimes suggested that Lord Hoffmann’s approach is an aberration in the common law of contract, which has consistently prioritised the meaning of the words over the parties’ apparent intentions. In fact, however, it bears a striking resemblance to the approach taken by the courts in sixteenth century England, where a very similar debate about interpretation was playing out. In a recently-published book chapter*, I explore this history and what it means for contract lawyers today.

I focus on a particularly interesting case from this period: Throckmerton v Tracy (1555) Plow 145, Dyer 124b, which concerned the lease of a piece of land in Gloucestershire. The lease was made in 1525 by Henry Beeley, the Abbot of Tewkesbury, to one John Smith. It was to run for 21 years, beginning after a pre-existing lease had ended.

Another local figure had also been interested in the land: Richard Tracy, a Protestant theologian and pamphleteer. Perhaps unsurprisingly, he was on bad terms with the Abbot, who refused to rent to him. In 1540, however, Tracy had a stroke of luck: Tewkesbury Abbey was dissolved, and the freehold of the land was surrendered to Henry VIII. It was now in the gift of Thomas Cromwell, who duly passed it to his close associate Tracy.

Despite this change in ownership, John Smith’s lease remained good, and began to run in 1542. But after Cromwell’s downfall, Tracy’s fortunes went into decline. In 1551 he was imprisoned in the Tower of London, where he was questioned by John Throckmorton. Perhaps Throckmorton wanted to keep an eye on Tracy, because in May 1552, with Tracy still in prison, Throckmorton bought the lease of Tracy’s land from John Smith.

Tracy was eventually released in November 1552, and was evidently disgruntled to find that Throckmorton, his erstwhile inquisitor, was now his tenant. In March 1553, Tracy seized Throckmorton’s sheep, provoking a lawsuit. His aim was to show that the Abbot’s lease was void, and that Throckmorton had no right to the land at all. He pointed out that the Abbot had made a serious drafting error: instead of granting the ‘possession’ of the land, the lease only mentioned a non-existent ‘reversion.’

The case was heard by the Justices of the Common Pleas between 1555 and 1556. (By this stage, Mary was on the throne; Throckmorton had been appointed as a Master of Requests; and Tracy had been twice reprimanded by the Privy Council for his religious activities.) In court, Throckmorton’s lawyers acknowledged the drafting error. If the word ‘reversion’ were given its ‘proper signification,’ they admitted, the lease would be void. However, they argued, the law ought to ‘draw the words from their proper and usual signification to fulfil the intention of the parties.’ It was ‘very apparent’ that the Abbot had intended to make an effective lease, so why quibble over technicalities?

The court was initially divided on the proper approach to the interpretation of the lease. Stanford, Saunders and Humphrey Brown JJ all agreed with Throckmorton. Stanford J, for example, held that the lease should ‘be construed according to the intent of the parties, and not otherwise,’ and that it should not ‘be void, where the words may be applied to any intent to make it good.’

Similarly, Saunders J argued ‘that contracts shall be as it is concluded and agreed between the parties, according as their intents may be gathered.’ He urged judges not to ‘cavil about the words in subversion of the plain intent of the parties,’ which was ‘a kind of trickery, and an excessively clever, but wicked interpretation of the law.’ Instead, they ought to ‘observe and follow the intent of the words’, which were ‘the testimony of the contract.’ Parodying literal interpretation, he cited Cicero’s example of a general who makes a truce for 130 days, but attacks his enemies during the night. Such interpretation, he warned, would only produce ‘injury and injustice.’

Brooke CJ, in contrast, declared that ‘there ought to be apt words to express the meaning, or else the meaning shall be void.’ If a party’s intentions were all that mattered, he would become ‘very careless about the choice of his words, and it would be the source of infinite confusion and incertainty to explain what was its meaning.’ Brooke warned darkly that ‘this would be the way to introduce barbarousness and ignorance, and to destroy all learning and diligence.’

However, he soon changed his mind. ‘Afterwards,’ reported Plowden, he said that ‘he was content that judgment should be given for the plaintiff’ after all. Dyer even recorded that Brooke had ‘prepared an argument on both sides, and if any one of his companions had been against the lease, he would have argued for it.’ And indeed, it was Saunders and Stanford JJ’s approach that prevailed in virtually all interpretation cases of the mid-sixteenth century.

In my chapter, I explore these approaches to interpretation further, examining their theoretical underpinnings and asking how they compare to views on contractual interpretation today. I argue that Lord Hoffmann’s approach hearkens back to sixteenth-century cases like Throckmerton v Tracy. Similarly, Lord Sumption’s criticisms mirror those made by Brooke CJ, which had become increasingly common by the beginning of the seventeenth century.

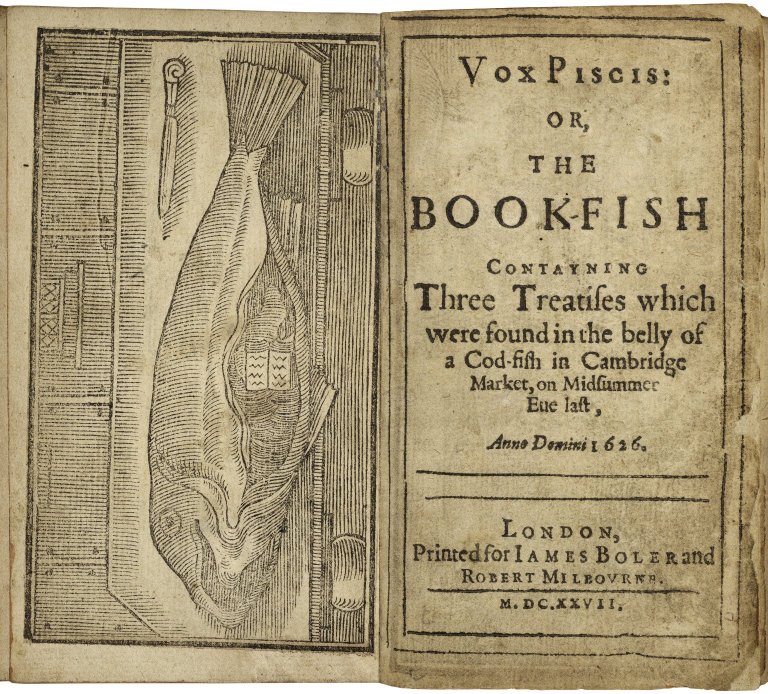

As for the two protagonists in our case: Throckmorton’s career ended in disgrace when he was imprisoned for giving judgment in favour of a family member. His son and heir was later executed for orchestrating the Throckmorton Plot against Elizabeth I. Tracy’s fortunes, in contrast, revived somewhat on Elizabeth’s accession to the throne, although he continued to agitate for a more radical religious settlement. One of his theological tracts became famous in 1626, when it was found inside the belly of a cod caught at King’s Lynn. No doubt he would have been pleased to know that it was interpreted as a warning of God’s imminent judgment, prompting a spate of anti-Catholic sentiment. Alas, it is not known how neighbourly relations between Tracy and Throckmorton played out in the remaining years of their lease.

* J McCunn, ‘Revolutions in contractual interpretation: a historical perspective’, in Worthington, Robertson & Virgo (eds), Revolution and Evolution in Private Law (Hart, 2018) ch 8. You can use the discount code CV7 for a 20% discount at the checkout.