by Robert Craig, the Law School, University of Bristol

The long awaited Bill seeking to reform the Human Rights Act 1998 (‘HRA’) was released on 22 June and is complex enough to cause an immediate outbreak of cold towels and hot-water-in-bowls amongst the legal Twitterati. No doubt there will be many hot takes on the substance of the new Bill of Rights Bill (‘BoRB’) but an early and fairly comprehensive analysis has been provided by Mark Elliott. For an even more aggressive response to BoRB see Daniella Lock on the UKCLA blog, published on 27 June. This post examines one slightly unusual aspect of the proposed new regime which is the effect of BoRB on legislation that has been expansively construed under s 3 HRA. This is by no means the only example of complications thrown up by the Bill and no doubt others will emerge in discussion on twitter and elsewhere. One well known legal commentator has amusingly described a particular twitter thread on 22 June as “legal geekery of the gods”.

Background

S 3 HRA requires the courts to attempt to make legislation comply with Convention rights.

So far as it is possible to do so, primary legislation and subordinate legislation must be read and given effect in a way which is compatible with the Convention rights.

The effect of this famous provision is well known. It places on the judiciary an obligation to interpret legislation expansively so as to comply with Convention rights.

BoRB removes that interpretive obligation entirely. It also removes the requirement in s 2 HRA that the courts take “into account” the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights. Instead, a complicated provision in clause 3 of BoRB requires the courts to ‘have particular regard’ to the text of the Convention and ‘the development under the common law of any right that is similar to the Convention right’.

It is clear, therefore, that BoRB removes the power of the courts to adopt an expansive interpretation of Acts in future, if it passes unchanged. What then of the previous broad interpretations of Acts under the old s 3 HRA regime? What happens at the moment the HRA is repealed, known as “commencement date” in BoRB (cl 40(7) below)? This post considers the possibility that all such expansive interpretations will also fall away if the new Act is passed in its current form.

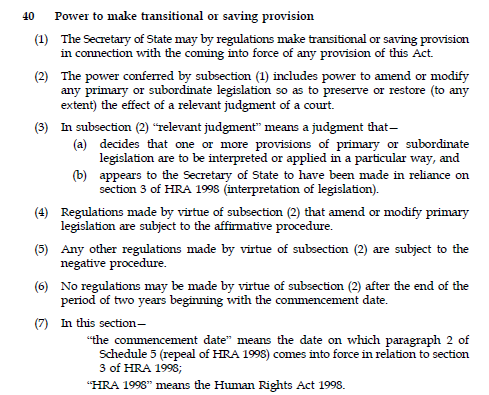

The primary evidence for this possibility is Clause 40 BoRB.

This needs to be read with paragraph 71 of the Explanatory Notes published alongside BoRB.

Clause 40 gives a power the Secretary of State to ‘preserve or restore’ the effect of ‘a relevant judgment of a court’. The reference to the “effect” of a “relevant judgment” is code for where a court has previously adopted an expansive interpretation of a particular provision of an Act of Parliament. On one reading, therefore, the Secretary of State has the power to maintain previous expansive readings of Acts by the courts whilst all the other examples of expansive reading would fall away. In other words, all the previous cases of expansive reading will be overruled, and the original wording of the Act will be applicable from commencement date of the BoR. As Kyle Murray points out, it is difficult to avoid the argument that a saving provision like this presupposes that unsaved changes otherwise fall away.

On another reading, nothing so drastic is meant. On this view, the expansive interpretation is maintained but clause 40 has been inserted as a ‘belt and braces’ provision in case there is any confusion about the meaning of the expansive interpretation in future.

Retrospective or prospective?

If the former interpretation is preferred, then a further question arises. Does the s 3 HRA expansive interpretation fall away ab initio or does the original wording retain its expanded meaning until commencement date?

To answer this question, we need to refer to s 16 Interpretation Act 1978.

This section preserves the effect of statutory provisions even after they are repealed. This prevents, for example, ancient statutes unexpectedly “reviving” when an Act that repealed them is itself repealed. For our purposes, s 16(1) (b) and (c) are relevant because they appear to preserve the “operation” of the enactment and any “right” that has been accrued during that period. This suggests that the meaning of the expansive interpretation of any Act is frozen until commencement day. This would mean that everyone is entitled to continue on the assumption that expansively interpreted legislation is unaffected until such time as BoRB passed into law.

What then of post-commencement date meaning of previously expansively interpreted legislation under s 3 HRA? Is that meaning also preserved by s 16 IA 1978? We don’t know. On one view, and this is where it gets tricky, the “meaning” of the legislation as interpreted under s 3 HRA was the “true” meaning because it was the actual meaning once parliamentary intention (both in the Act and the HRA) was discerned by the court. On this view, this “true” meaning would therefore persist even after commencement day. This would make clause 40 a mere saving provision in case of confusion rather than a root and branch change such that any expansively interpreted provision of the last 24 years would need to be positively approved and retained by the Secretary of State via secondary legislation.

On another view, the repeal of s 3 HRA would cause the expansive interpretation to fall away from the commencement date (s 16 IA 1978 would preserve the previous effects) and the “original” meaning of the statutory provision that had been expansively interpreted would suddenly return (but only prospectively). This could have dramatic effects on settled practices and assumptions of how various legislation is understood in a number of areas. There would doubtless be much urgent lobbying of the Ministry of Justice to restore the settled practice in many areas. When reading paragraph [71] of the Explanatory Notes excerpted above it is tolerably clear that the drafter thinks that the s 3 HRA expansive interpretations will indeed fall away.

I would also draw the reader’s attention to Colm O’Cinneide’s excellent point on twitter that the courts have frequently been unclear as to whether their particular interpretation of an Act was brought about by s 3 HRA or by standard alternative interpretative approaches. The meaning of cl 40 is not sufficiently clear but it should be noted that cl 40(3)(b) leaves it to the Secretary of State to decide if it “appears” to him or her that the interpretation in question was made in reliance on s 3 HRA. I cannot see how the complexity highlighted in this post would be resolved as it stands judicial consideration. Of course, it is possible that further clarity is achieved during the passage of BoRB through parliament.

There is also a two year time limit on the power of the Secretary of State to introduce secondary legislation to restore or preserve the meaning of particular legislation. As Henry VIII clauses continue to proliferate, the time sensitive aspect of this particular controversial statutory-amending power is to be welcomed.

Conclusion

The proposed reforms to the HRA are significantly more ambitious than many commentators expected, especially in relation to the duty of interpretation under s 3 HRA. The removal of that power possessed by the courts is a genuine surprise. The potential attempt to remove the effect of previous s 3 HRA expansive interpretations for the future is an even bigger surprise. Overall, the clear impression of an attempt to reduce the effect of human rights claims on statutory provisions is clear and unequivocal.

Thanks to Stefan Theil for his helpful comments on a previous draft and to Foluke for editing and posting it. The usual disclaimer applies. The views in this thread are the author’s own.

It wasn’t a surprise to anyone who did the consultation.

And I don’t agree the reforms are ambitious. I think they don’t go far enough.

As for Mr Elliott, he spent a long time on Twitter trying to stop the Government getting us out of the EU, so he is firmly in the category of ‘activist’.