by Antonia Layard, Professor of Law, University of Bristol Law School

In Scotland, children and young people will have free bus travel in 2021. They join children and young people in London who also have free travel, seeing off an attempt to take the concession away through a feisty #don’tzapthezip campaign last year. Since 2008, older and disabled people have even greater concessions, able to catch a bus anywhere in England after 9.30am on weekdays as well as all day at weekends and on bank holidays, receiving subsidised travel as part of the English National Concessionary Travel Scheme (ENCTS).

Elsewhere in England and Wales, however, children and young people very rarely have free bus travel. In last week’s Strategy document, the curiously titled, three word slogan, Bus Back Better, the Government stated categorically that “We will not fund travel for people who are not necessarily disadvantaged, such as blanket free travel for unaccompanied children …”.

While 53 local authorities (including Bristol) provide additional concessions for older people to use buses for free before 9.30am on a weekday, only 18 local authorities provide financial support to subsidise children and young people’s fares. This select crew of local authorities who support children’s travel does not yet include Bristol, though this may change given the verbal pledge by Marvin Rees, the Mayor, to introduce an aim into Bristol’s One City Plan to achieve free travel for children under 18 (at 1.54.56 in the Recording for Full Council Tuesday, 16th July, 2019). Bristol’s 2021 One City Plan now commits to introducing free bus travel for children aged 16-18, in part to address some of the most unequal educational outcomes in the country, acknowledging that reaching a post-16 centre of choice often depends on being able to afford the bus fare to get there.

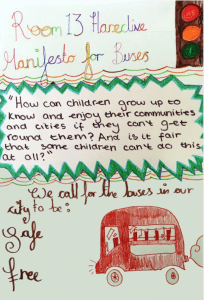

For younger children, however, buses can still be unaffordable, limiting children’s lives. This lack of free or affordable bus travel has enormous consequences for children living on some of Bristol’s most economically deprived streets. As the children in Room 13 ask in their campaigning film Now’s the Time, which calls for free buses for children:

“My family don’t own a car and the bus fares are so expensive. Lots of people can’t get into Bristol to experience the city centre. Some children have never been into Bristol yet they only live a few miles away. So I want to ask you: how can children grow up and enjoy their cities if they can’t get around them? Is it fair that some children can’t do this at all?”

Our research at the University with Room 13 Hareclive E-Act has worked with children, using studio-based arts-led methods, including a film written, directed and acted by the children as well as a primary school-wide survey, semi-structured interviews with twelve transport experts as well as extensive legal and policy research, to produce a report and Policy Bristol note, summarising our findings and calls for change.

We found that the lack of affordable access to buses for children in Bristol affects lives, inhibiting access to activities, sports, leisure, arts, culture, skate parks and history in their city? As one parent told us:

“If I take my children to the dentist, it’s 4 stops away but I have to pay £1 each there and back again with the £4 I have to pay for myself – that’s £8 [today the price would be £9], which is a week of electricity for us at home”. [Parent]

A character in the film drew on a child’s experience the year before:

“My Ruby broke both of her arms last year and we were in and out of hospital with appointments for weeks. It cost a fortune.” [Character in Now’s the Time film]

As the film’s narrator declares: “Clearly there is a problem.”

The lack of support for children and young people’s travel rests on a series of choices, in particular, the deregulation of bus travel by the Transport Act 1985, since when bus prices have increased far more quickly than motoring costs; the choice to subsidise all older and disabled people rather than any children or young people and the focus on quality contracts, partnerships and supported routes to strengthen bus networks rather than focusing on subsidising children as a category of passengers, a power long provided by section 93(7) of the Transport Act 1985.

Free bus travel can increase active hobbies, promote connection and a sense and belonging as well as developing travel socialisation. It also makes common sense, as ‘Stan the Bus Driver’ explained in the film, Now’s the Time:

“If bus travel was free for children until they left education it would be better for ALL of us in the long run. It makes economical sense as children will grow up to be adults that will use buses more, which is good for the bus companies, for congestion, the planet and all our health.” [Room 13 film script – Stan the bus driver]

In England, free bus fares for children are not yet on the policy agenda, Bus Back Better indicates that such a reform does not have Government support. Indeed, calls for children’s concessions are often met with arguments that we should level down, rather than up.

Instead of supporting free bus fares for children and young people, the Thinktank Policy Exchange ‘questioned the fairness’ of the current scheme for older people using a localised example that rarely applies. In London, Transport Secretary Grant Shapps responded to concerns about cutting children’s access to public transport by criticising the management of Transport for London (TfL), particularly the decisions taken by Sadiq Khan, the London Mayor. The Secretary of State attempted to make cuts in children’s travel a condition of lockdown transport support for TfL, so that “people in other parts of the country do not unduly subsidise London”. These inter-generational and locational differences in access to free bus travel are at risk of being reduced to the lowest common denominator, although as the (temporarily) successful #dontzapthe zip London campaign showed, this would be quite a political task.

Why should children have free bus fares outside London or Scotland, perhaps on a par with older and disabled people? Making their move for children and young people, the Scottish government has outlined both the transport and social advantages of the new concessionary scheme as encouraging children and young people:

“to use low-emission and lower carbon public transport with a view to embedding that behaviour from a young age, to tackle the climate emergency and to improve air quality in towns and cities by reducing the number of car journeys” as well as promoting “social inclusion (by improving access to education, healthcare, training and employment etc.) and reduction in child poverty…”

In London, in a major set of studies investigating the impact of free bus travel for children in 2005, the findings included a greater sense of belonging as well as cleaner and less dangerous streets. The 2016 evaluation of the English concessionary scheme for older and disabled passengers found that the concession meets its stated aim “to increase the ‘quality of life’ for concessionary travellers” interpreting this as ‘well-being’, ‘physical and mental health’, ‘standard of living’, ‘recreation and ‘leisure time’ and ‘social-belonging’ even if detailed causation is hard to find. Last, but not least, concessionary bus travel is decidedly electorally popular.

Yet elsewhere, in Bristol, not being on the buses constrains children’s leisure, their active hobbies such as sports clubs and outdoor play as well as independent mobility and socialisation. In the film’s dream sequence, the children muse about what they might do if they could travel for free:

“I would really want to go to the skate park but with travelling it would just cost too much. It’s the same about me for dance classes [child characters].”

“There are brilliant free events in the city centre and parks we could go to but the roads just aren’t safe enough for children to walk or cycle.” [child character]

The cost to Government of concessionary passes is extraordinarily cheap – in 2018/19 (pre-pandemic) the average reimbursement per pass was £83 per year in England outside London, costing £662 million. While this is a significant part of the overall bus budget, it is far less than we spend on trains (where the Government provided £6.5bn of support for the operational railway, £1.8bn in funding for enhancements to the existing network and £2.5bn towards High Speed 2), even though people in the highest income quintile made over three times more rail trips each on average compared to those in the lowest. Buses have been consistently, relatively, underfunded, with declining government support and new interventions aimed at improving the bus fleet and bus priority – undoubtedly important aims – rather than helping vulnerable children use buses. This lack of passenger support continues even though buses are overwhelmingly used by those with fewer economic resources, particularly women, older and younger people with bus fares continuing to rise.

This low price for concessions admittedly comes with growing concerns, in both England and Scotland, that the reimbursement policy can have unintended consequences, for example, distorting bus geographies (creating popular tourist routes where almost all passengers are concessions, for which operators receive a below average fare), risking the viability of less profitable routes if margins become tight and, particularly, if children and young people use concessionary bus passes to get to school or college, creating difficulties for operators at peak morning rush hour.

Yet if the political ambition exists to support children and young people throughout England, in the way we rightly support older and disabled people, there are many ways the funds could be raised – including from workplace parking levies (which fund much of Nottingham’s tram system), congestion charging (part of the London mix), combined authority funding to help young people post-16 or out of general revenue. All of these are spelled out in our report.

Ultimately, this is a question of political will. The Scottish Government has allocated £15 million for free fares for children and young people in 2021-22 (just over 5% of their existing budget for supported bus services). In England, meanwhile, while the Transport Select Committee have repeatedly acknowledged the importance of free bus travel for children, young people and apprentices, this money is never found. Local authorities often prioritise ‘add ons’ for older passengers rather than support children and young people.

The children at Room 13 in Hartcliffe, who live on some of the most deprived streets in England, just four miles from our University via some of the most reliable bus routes in the city, are campaigning for the long haul.

If the children wait long enough, when they reach retirement age, the free bus will finally come.