By Dr. Georgina Tsagas, Senior Lecturer in Law (Brunel University) and Prof Charlotte Villiers, Professor of Company Law (University of Bristol Law School).

In our paper we shed light on why ‘Less is More’ in the Non-Financial Reporting landscape and explain how an effective decluttering of the non-financial reporting landscape can take place by focusing on improving and widening the scope of the application of the EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive.

In our paper we shed light on why ‘Less is More’ in the Non-Financial Reporting landscape and explain how an effective decluttering of the non-financial reporting landscape can take place by focusing on improving and widening the scope of the application of the EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive.

What is the root cause of the problem at hand?

Knowing ‘the price of everything and the value of nothing’ is more than just a nice turn of phrase that Oscar Wilde had Lord Darlington quip in one of his plays. Projecting into the future, the phrase has spoken volumes on how modern society has drifted away from cultural values and has also highlighted society’s collective failure to place those values on a par with financial ones. Yet in the area of corporations’ non-financial reporting the problem remains that, although in the year 2020 we have reached a common ground on the fact that sustainability is a value worth preserving, there is no rate, no metric, no price nor cost attached to it, which arguably creates chaos for private and public actors alike. Not only do identified stakeholders face the negative consequences, but in both the short term and long term all actors involved and affected corporations, as well as society as a whole, will face the adverse effects of corporations’ unsustainable practices. The fact that sustainability cannot be accounted for in a consistent way is the essence of the problem. Assuming that the chaotic framework for non-financial reporting is part of the problem, we argue that fixing that framework must be part of the solution.

Why is the discussion topical now?

Steps are being made in the right direction towards clarifying metrics around sustainability as addressed in the White Paper by the World Economic Forum published in January 2020, Toward Common Metrics and Consistent Reporting of Sustainable Value Creation. Also, at EU level, proposals for reform are now likely to be forthcoming , following a consultation exercise by the European Commission that had commenced in January 2020.

What was the case for introducing non-financial reporting in the first place?

For years governments have taken solace in the idea that corporations’ transparency on their corporate activity in relation to sustainability through voluntary reporting is adequately addressing the problem. It is evident however that in practice, non-financial reporting is failing to deliver truly sustainable results. Why is this so and what can be done? To address these questions, we consider more specific ones in our paper. How does the varied reporting landscape in the field of non-financial reporting impede the objectives of fostering corporations’ sustainable practices? Which initiative, among the options available, may best meet the sustainability objectives after a decluttering of the landscape takes place?

Why is this issue topical and of significance? Climate Crisis, Reform, Metrics, Excessive Choice and Purpose

Climate Crisis & the NFRD (content and reform process): Corporations supply products and services, and they contribute towards an increase in energy use and carbon emissions that leave a carbon footprint. Corporate contribution to climate change is so clear that it merits policy makers’ primary attention in terms of prompting corporations’ efforts to reduce global warming and carbon emissions. Industrial activities of corporations of all sizes provide the link between human action and global warming. This is documented by authors such as Wright and Nyberg who observe in their book Climate change, capitalism, and corporations (Cambridge, 2015, at 3) that corporations are the ‘principal agents’ of greenhouse gas emissions. Certain companies in particular have been identified as responsible for emitting nearly two-thirds of industrial carbon dioxide, and a small number of carbon producers are responsible for methane emissions as well as 83 producers of coal, oil, natural gas and 7 cement manufacturers, contributing to a rise in atmospheric concentrations of CO2 and CH4, GMST and global sea level.[1] Numerous scientific reports have also recently raised the bar with regard to the enormity of the threat. In May 2019 the Report published by the Intergovernmental Science Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services noted the real risk of losing a million species, threatening the continued existence of humans too.[2] Another recent report warns that there are only 12 years left to act meaningfully in order to avoid catastrophic levels of global warming with corporations having played a central role in bringing about this global warming threat.[3]

In response to the impact of corporate activity on the environment and on society multiple initiatives have been developed to encourage or demand that companies report on their activities. Such initiatives, voluntary and mandatory, operate largely on the assumption that if a company’s activities are opened up to the world their impacts can then be measured, stakeholders can judge how beneficial or harmful they are and shareholders can decide if they are the right companies in which to invest. Our paper highlights the enormous variety of global and national voluntary CSR, ESG and sustainability reporting standards, principles and guidelines. Arguably the most comprehensive mandatory legislation is the European Non-Financial Reporting Directive which was adopted in 2014 and has since been implemented in Member States across the European Union. Applying to large public-interest companies with more than 500 employees, (approximately 6,000 large companies and groups across the EU, including listed companies, banks, insurance companies and other companies designated by national authorities as public-interest entities). Such undertakings are required to provide

“a non-financial statement containing information to the extent necessary for an understanding of the undertaking’s development, performance, position and impact of its activity, relating to, as a minimum, environmental, social and employee matters, respect for human rights, anti-corruption and bribery matters, including: (a) a brief description of the undertaking’s business model; (b) a description of the policies pursued by the undertaking in relation to those matters, including due diligence processes implemented; (c) the outcome of those policies; (d) the principal risks related to those matters linked to the undertaking’s operations including, where relevant and proportionate, its business relationships, products or services which are likely to cause adverse impacts in those areas, and how the undertaking manages those risks; (e) non-financial key performance indicators relevant to the particular business. Where the undertaking does not pursue policies in relation to one or more of those matters, the non-financial statement shall provide a clear and reasoned explanation for not doing so.”

The general aim of the Directive of 2014 is three-fold: i) to improve the quality of non-financial reporting across the EU; ii) to allow greater comparability; and iii) to attract inward investment. More specifically, as provided for by the Directive itself, its objective is ‘to increase the relevance, consistency and comparability of information disclosed by certain large undertakings and groups across the Union’ and essentially aims for non-financial information published by undertakings to become more consistent and comparable. However, the Directive does not guarantee improved ESG behaviours. Companies that do not have policies on the subject matters identified may choose to provide minimal disclosure through the Directive’s comply or explain format, requiring them only to explain why they do not have such policies in place. The flexibility and discretion given to undertakings in what and how they disclose does little to improve consistency and comparability in reporting across the corporate sector. Reform is on its way. Steps are being made in the right direction towards clarifying metrics around sustainability as addressed in the White Paper by the World Economic Forum published in January 2020, Toward Common Metrics and Consistent Reporting of Sustainable Value Creation. Also, at EU level, proposals for reform are now likely to be forthcoming , following a consultation exercise by the European Commission that had commenced in January 2020.

Metrics: To support the function of the market towards sustainability, metrics are required. The Efficient Capital Market Hypothesis posits that markets serve as a more objective institution in which an exchange of information takes place with the use of metrics and that, key to the proper function of a stock market that behaves rationally, share prices reflect the company’s performance and future prospects. However, this hypothesis has been heavily criticised.[4] Not least, in the words of Ha-Joon Chang, observing more generally the problems relating to capitalism, including the workings of the market as such: “People ‘overproduce’ pollution because they are not paying for the costs of dealing with it.”[5] Moreover, market pricing is unlikely to reflect the sustainability of a corporation within its broadest sense, since all relevant information on CSR practices is still not publicly available through mandatory and systematic reporting. One important area for reform therefore is to widen the target group and for initiatives to be steered by metrics that will help markets reveal unsustainable behaviour towards people and planet.

Excessive choice and Purpose: Reed et al. find that although organisms prefer to make their own choices, emerging research from behavioural decision-making sciences has demonstrated that many decisionmakers find an extensive array of choice options often leads to negative emotional states and poor behavioural outcomes.[6] The excessive choice offered to companies, in terms of what and how they will report in the sustainability arena, gives rise to serious problems from a behavioural economics perspective. The variety of choice of voluntary reporting in the context of sustainability leads to uncertainties surrounding the utility of the information corporations are required to provide. Referring to what is known as the “Sisyphus effect”, behavioural economics scientists, Ariely et al, investigate how the importance of finding purpose in any task influences labour supply and productivity.[7] Transposed to the area of sustainability reporting, the pointlessness of the task of non-financial reporting for most corporations easily explains companies’ unwillingness to engage in this activity beyond compliance and a box-ticking exercise. The overabundance of choice and the quest for more meaningful reporting point to a need to clean up the existing non-financial reporting landscape by making clearer the target recipients, connecting the required disclosures more closely to their needs and clarifying what is meant by the concept of materiality for non-financial reporting purposes.

Why are there so many initiatives in the non-financial reporting arena?

The notion of sustainability per se, continues to remain a contested concept and varied interpretations of the term are available. Variances between companies and industries in relation to how each is operating, sustainably or unsustainably, also continue to exist. Such variances have so far inhibited drafting tailored legislation to reflect the individual risks to global sustainability in an all-encompassing manner. However, the end product is a chaotic system of financial reporting, CSR reporting, non-financial reporting and integrated reporting. As a result, policy makers are falling far short of the objective of increasing comparability and credibility as they seek for companies to be held accountable and to behave in ways that do not harm the people and the planet.

Why should we focus on the NFRD over other initiatives?

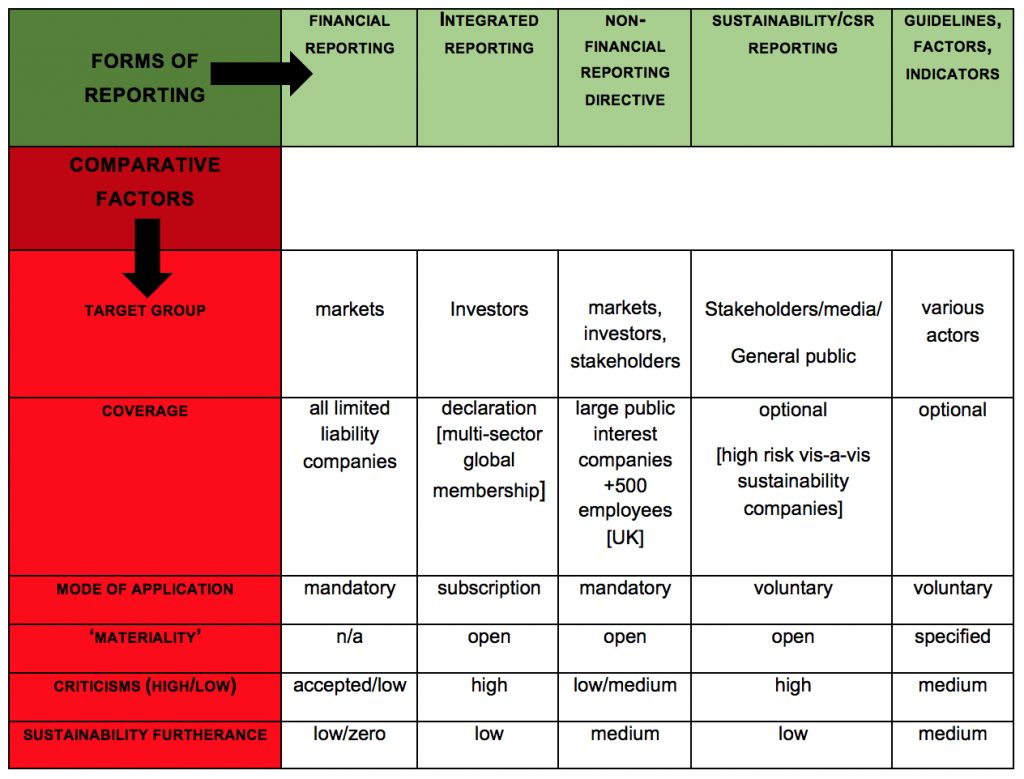

Using deductive reasoning, in our paper, we compare particular initiatives and find that out of all, the NFRD positively ticks more boxes from the selected factors. The factors refer to the targeted recipients of each initiative, the companies it covers, its mode of application, whether it reflects on the issue of “materiality”, and the extent to which the initiative is in fact found to further sustainability objectives. Our paper concludes that policymakers should focus their attention on reform of the NFRD specifically for the purpose of realising an effective decluttering of the non-financial reporting landscape. The sources of data for the construction of this table are provided from academic literature devoted to discussing the different initiatives, the primary source of the text of each initiative itself and reports on the application of each initiative following its adoption.

Table 1: Forms of Reporting Initiatives and Systematic Comparison

Despite its own limitations, the NFRD can be seen as “an important incremental step” towards “mainstreaming sustainability reporting as mandatory rather than optional”.[8] One of its major contributions is to inspire action by governments and individual entities and it might be viewed as a catalyst to encourage more detailed and varied ways of bringing about corporate and stakeholder engagement in reporting and sustainability processes.[9]

Contribution and Conclusion

Random and arbitrary compliance with various initiatives makes companies’ sustainable practices “less” transparent instead of “more”. Our paper offers a comprehensive view on different reporting frameworks. It shows that there is a need to provide some clarity in this complex landscape. Fundamentally, the current reporting landscape, is unlikely to impact positively on efforts towards sustainability. We suggest that the scope of the NFRD, as the most promising of the existing initiatives, should be revisited so as to enhance its contribution to furthering corporations’ sustainable practices. Our paper supports reform of the NFRD which has constituted a positive step in the right direction. What is required now is stronger guidance on what to report and how to report it. Steps are being taken in the right direction towards clarifying metrics around sustainability.[10] A standardized and streamlined framework is necessary in order to pin companies down to something more concrete, rather than giving to them too much choice on which guidelines, frameworks or recommendations they may opt to follow. Stronger, clearer and more concrete definitions of key concepts are required, as well as clarification of the rights of stakeholders in this area of activity. Proposals for reform that have arisen, with a consultation exercise by the European Commission[11] are therefore to be welcomed. We suggest an expansion of the NFRD’s scope and that it represent sustainability as a positive instead of reducing the focus only onto negative risks. Member States and companies should have opportunities for effective compliance with the reporting requirements, with the NFRD better defining the concepts it refers to.

[1] Heede R (2014) ‘Tracing anthropogenic carbon dioxide and methane emissions to fossil fuel and cement producers 1854–2010’ Climatic Change 122: 229–241; Ekwurzel, B., Boneham, J., Dalton, M. W., Heede, R., Mera, R. J., Allen, M. R., & Frumhoff, P. C. (2017) ‘The rise in global atmospheric CO2, surface temperature, and sea level from emissions traced to major carbon producers’ Climatic Change, 144(4), 579–590.

[2] Brondizio E.S., Settele J., Díaz, S. and Ngo H.T., (editors) (2019) Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science- Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. (IPBES Secretariat, Bonn, Germany).

[3] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (UN) Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C, (SR15) at https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sr15/.

[4] There is a vast literature on the efficient capital markets hypothesis. See in particular Fama EF (1970) ‘Efficient capital markets: a review of theory and empirical work’ J Finance 25: 383–417 and Fama EF (1991) ‘Efficient capital markets: II’ J Finance 46:1575–1617. For a review of the arguments on both sides of the debate see e. g.: Malkiel, B. G. (2003) ‘The efficient market hypothesis and its critics’ Journal of economic perspectives, 17(1), 59–82; and Naseer, M., & bin Tariq, Y. (2015) ‘The efficient market hypothesis: A critical review of the literature’ IUP Journal of Financial Risk Management, 12(4), 48–63.

[5] Ha-Joon Chang ‘23 Things They Don’t Tell You about Capitalism’ Penguin Group: London, UK, 2010.

[6] Reed, D.D., Kaplan, B.A and Brewer, A.T ’Discounting the freedom to choose: Implications for the paradox of choice’ Behavioural Processes 90(3) (2012) p. 424–427.

[7] D. Ariely, E. Kamenica and Drazˇen Prelec “Man’s search for meaning: The case of Legos” Journal of Economic Behaviour & Organization 67 (2008) 671–677.

[8] Ahern, Deirdre. “Turning Up the Heat? EU Sustainability Goals and the Role of Reporting under the Non-Financial Reporting Directive.” European Company and Financial Law Review 13.4 (2016): 599–630, at 629.

[9] Camilleri, M.A., ‘Environmental, social and governance disclosures in Europe’ (2015) 6:2 Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 224–242.

[10] See eg World Economic Forum, Toward Common Metrics and Consistent Reporting of Sustainable Value Creation https://www.weforum.org/whitepapers/toward-common-metrics-and-consistent-reporting-of-sustainable-value-creation

[11] See Non-financial reporting by large companies (Updated rules) public consultation of European Commission 2020 at https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/12129-Revision-of-Non-Financial-Reporting-Directive