By Dr Albert Sanchez-Graells, Reader in Economic Law and Member of the Centre for Health, Law, and Society (University of Bristol Law School).

As Brexit day approaches and the UK and the EU fail to complete their negotiations for a withdrawal and transition agreement to ensure an ‘orderly Brexit’, more and more voices will raise strong concerns about the impact of a no-deal Brexit for important sectors of the UK economy and public sector. In a leaked letter, the trade association of NHS providers sent a clear warning message to the public bodies in charge of running the English NHS (NHS England and NHS Improvement). As widely reported by the press, NHS providers made it clear that poor co-ordination by ministers and health service bosses means there has been a failure to prepare for the UK to be left without a Brexit deal, and that this could mean “both stockpiles and shortages of medicines and medical devices”.

As Brexit day approaches and the UK and the EU fail to complete their negotiations for a withdrawal and transition agreement to ensure an ‘orderly Brexit’, more and more voices will raise strong concerns about the impact of a no-deal Brexit for important sectors of the UK economy and public sector. In a leaked letter, the trade association of NHS providers sent a clear warning message to the public bodies in charge of running the English NHS (NHS England and NHS Improvement). As widely reported by the press, NHS providers made it clear that poor co-ordination by ministers and health service bosses means there has been a failure to prepare for the UK to be left without a Brexit deal, and that this could mean “both stockpiles and shortages of medicines and medical devices”.

NHS providers have thus requested that the Department of Health and Social Care, NHSE and NHSI accelerate preparations for a no-deal Brexit. In this post, I argue that there is very limited scope for no-deal preparations concerning medical equipment and consumables, and that this can have a very damaging impact on the running of the NHS post-Brexit, given that it annually spends approximately £6 billion on goods (such as every day hospital consumables, high cost devices, capital equipment and common goods).

NHS procurement of medical equipment and consumables

As I explore in a recent paper*, the NHS acquires medical equipment and consumables in a very complicated way. NHS trusts in need of specific equipment or supplies have three options: they can procure them directly from private providers, they can collaborate with other trusts to procure them together, or they can buy them from a centralised entity running the NHS Supply Chain (NHS SC). NHS SC thus offers centralised procurement services to the English NHS, in an attempt to streamline procurement procedures and to achieve economies of scale by accumulating the NHS’ buying power in a single entity.

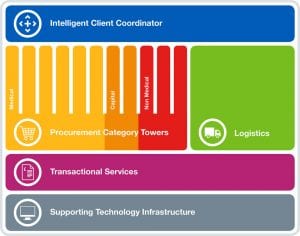

Currently, NHS procurement is roughly split as 20% solo procurement by NHS trusts, 40% collaborative procurement, and 40% centralised procurement through NHS SC. Given the potential for savings that the Department of Health and Social Care sees in further NHS procurement centralisation, it launched a new procurement strategy—the ‘New Operating Model’ (or NOM)—to increase centralised procurement to 80% of NHS expenditure and thus unlock annual savings of £615 million from 2022/23 onwards. The NOM relies on a number of private entities acting as ‘category tower service providers’ (CTSPs) entrusted with establishing and implementing procurement strategies for the entire NHS. All CTSPs have been chosen over the last 12 months and most of them are still in the early stages of developing full-fledged NOM strategies and procedures. The NOM should be fully operational from October 2018, but there have been significant delays, in particular concerning the award of a contract for the logistics services underpinning the NOM.

Logistics are a key aspect of centralised procurement, as the distribution of centrally-acquired medical devices and consumables to all NHS trusts has immense operational importance. Until October 2018, the logistics of NHS SC will have been run by the private operator DHL. As part of the NOM, NHS SC tendered a new logistics contract. DHL lost the tender, and the contract was awarded to a competing logistics operator (Unipart). As recently reported, DHL challenged the award of the contract to Unipart, but the High Court has provisionally decided that NHS SC can go ahead and start implementing the NOM with Unipart—with DHL left only with a claim for damages if the award is finally found to have breached the applicable procurement rules. DHL has appealed this decision in order to extend the suspension of the award to Unipart. At the time of writing (23 August 2018) a final decision is pending.

On the whole, this litigation is generating delays, uncertainty and additional cost in the implementation of the NOM. As things stand, it seems likely that, in the coming months, NHS SC will have to transition to a new logistics operator, at the same time as it seeks to scale up its activities. In the alternative, if DHL wins the appeal, NHS SC may end up having to re-run the procurement, which would create additional delays. One way or another, this is a period of transition into a very complex procurement system that, on its own, already generates uncertainty and operational risks for the NHS.

No-deal Brexit, the last thing NHS procurement needs

In the context of the implementation of the NOM, a no-deal Brexit is the last thing that NHS procurement needs. Establishing a strategy to ensure continuity of supply of medical equipment of devices (including, if appropriate, their stockpiling beyond normal levels) would be enormously complex and costly. NHS providers have clearly indicated that they consider that this should be done centrally, rather than “expecting trusts to develop contingency plans individually, in a vacuum, and have to reinvent the wheel 229 times”. Such a centrally-led approach to preparing NHS procurement for a no-deal Brexit should naturally fall on NHS SC. However, given that it is involved in its own (complex and protracted) transition into the NOM, this does not seem very promising.

Moreover, it needs to be taken into account that the entire NOM strategy rests in a complex mesh of outsourced contracts under the operational responsibility of private operators (mainly, the CTSPs mentioned above). Getting those private operators to change their strategies and procedures to adjust for no-deal Brexit would probably require a renegotiation of their own contracts—which would in itself take time and be costly. In the alternative, the Government could decide to take some of the NHS procurement operations in-house (eg emergency readiness only), but this would certainly destabilise the NOM and affect its implementation. More importantly, creating buffer in the system (eg through additional stockpiling) would be very costly—to begin with, in storage and distribution costs, which would naturally fall on the logistics operator. If the Government expects private operators to absorb those costs—as it has been more generally suggested regarding food stockpiling—this seems a naïve strategy. Sooner or later, those costs will be picked up by taxpayers.

All in all, then, I think there is very limited scope for no-deal preparations concerning medical equipment and consumables. Similar difficulties will arise concerning the supply of medicines, which are acquired separately by the NHS. And these difficulties will replicate themselves in every other sector of the economy and every other main part of the public sector. In view of this, I can only add my voice to Prof Syrpis and insist that it is time to stop Brexit.

__________________

* The full paper is freely available: A Sanchez-Graells, ‘Centralisation of Procurement and Supply Chain Management in the English NHS: Some Governance and Compliance Challenges’ (August 9, 2018). https://ssrn.com/abstract=3232804.