By Prof Jonathan Burnside, Professor of Biblical Law (University of Bristol Law School).

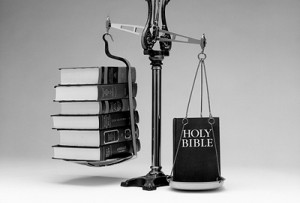

Biblical law is certainly an area where perceptions are key. Even if you don’t know very much about biblical law, you’ll likely have an opinion about it.

What does biblical law make you think of? What associations spring to mind, especially when you turn off the internal editor? For some of us the associations are primarily negative. We might see it as being out-of-date, violent or misogynistic. Our perceptions may be profoundly moulded by the fact it has the death penalty for certain offences. For some of us, our associations may be exactly the reverse. We might see biblical law as being ethically relevant – authoritative, even. We may see it, positively, as being concerned with liberating the oppressed, protecting the weak, and seeking justice.

Yet regardless of how we might imagine biblical law, the historical fact is that biblical law is a remarkable body of law. This is partly because of the sheer length of its continuous history of transmission and interpretation. It’s also because the Bible is said to be the most important book for making sense of Western civilisation and biblical law is one of its foundations. Whether it’s the idea of a shared day of rest, the constraints upon political authority, the idea of mercy or employee rights, biblical law has a claim to historical influence that’s unmatched by any other ancient legal system. A few years ago, a United States Supreme Court Judge claimed that the depictions of Moses with the Ten Commandments in the US Supreme Court building, and throughout Washington D.C., “testifies to the popular understanding that the Ten Commandments are a foundation of the rule of law, and a symbol of the role that religion played, and continues to play, in our system of government.” Writing in the Cardozo Law Review a few years ago, Bernard Levinson described the book of Deuteronomy as “the most ancient antecedent of the US constitution.” So whether we are aware of it or not, a lot of what we do as lawyers is an indirect engagement with biblical law. It’s rather like the claim that an understanding of the Bible is something you need to study English literature. This means, perhaps surprisingly, that the better we understand biblical law, the better we understand law.

To this we may add the fact that biblical law is also regarded as normative by many people. To borrow a phrase from Eugen Ehrlich’s sociology of law, biblical law is a ‘living law’ in the sense that it provides a normative context for ethical decision-making in church and synagogue, structuring everyday social relationships and social associations.

The irony is that, despite all this, biblical law is not well understood; either by the culture or by those who claim to see it as normative for their lives. (I might mention the biblical laws relating to the environment, social welfare, and immigration, to give just a few examples). I call this the problem of the ‘immanence’ of biblical law. In other words, biblical law is part of our culture, but it is alien. It’s unfamiliar to us, yet it is also in our midst. So it’s not surprising that our perceptions of the subject are rather contradictory and ambivalent.

In my research on biblical law, I see myself as trying to help us to get a better handle on this subject, most recently in my book God, Justice and Society (Oxford: Oxford University Press). It seems to me that the study of biblical law is all the more necessary at a time when we are increasingly aware that we cannot shut religion out of the public square. Even radical postmodern thinkers such as William Connolly have concluded that “the time of the secular modus vivendi is drawing to a close.” Regardless of how we try to address the issues raised by religion and politics, we need to understand the nature of the material we are dealing with. We can set the question of imagining biblical law in the broader context of legal pluralism, which acknowledges that there are competing accounts of the purposes of law and the derivations of those purposes. And so in understanding the nature of this pluralism and engaging with it, individuals and groups who are part of the biblical tradition need to understand how to handle biblical law.

Yet even though it is the case that the better we understand biblical law, the better we understand law, the task of imagining biblical law is too important to be left to lawyers. It’s also too important to be left to theologians! Because the better we understand law, the better we understand biblical law. That’s not always how biblical law has been understood but it is part of how it needs to be understood, and the study of law helps us to do that.

What all this means is that there is great value in a conversation between biblical law and modern law. When we engage in that we find that two things happen: that biblical law becomes less strange and modern law becomes less familiar. It makes the strange familiar and the familiar strange. We find there is more in biblical law than we first realised, and there are aspects of modern law we see in a different light.