By Miss Rose Slowe LLM, Senior Research Fellow (University of Bristol Law School).

With the Supreme Court having ruled on 24 January 2017 that Parliament must have a say in the triggering of Article 50 TEU, the ensuing debate regarding the process for exiting the EU has revolved around what is politically considered the most desirable ‘type’ of Brexit, and whether MPs can restrict the Government’s negotiation position. This post puts forward the hypothesis that such debates may be irrelevant because, in the event that negotiations fail, the UK has no guaranteed input on the terms of its withdrawal from the EU. At the heart of this problem is the still unanswered question whether an Article 50 notification is revocable (Prof Syrpis).

With the Supreme Court having ruled on 24 January 2017 that Parliament must have a say in the triggering of Article 50 TEU, the ensuing debate regarding the process for exiting the EU has revolved around what is politically considered the most desirable ‘type’ of Brexit, and whether MPs can restrict the Government’s negotiation position. This post puts forward the hypothesis that such debates may be irrelevant because, in the event that negotiations fail, the UK has no guaranteed input on the terms of its withdrawal from the EU. At the heart of this problem is the still unanswered question whether an Article 50 notification is revocable (Prof Syrpis).

In R (on the application of Miller and another) v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union [2017] UKSC 5, the Supreme Court rejected the Government’s appeal and upheld the High Court’s ruling that the royal prerogative cannot be relied on to trigger Article 50. Rather than reliance on executive power, an Act of Parliament is required to authorise ministers to give notice of the UK’s intention to withdraw from the EU. This is based on the premise that such notification under Article 50(2) would inevitably, and unavoidably, have a direct effect on UK citizens’ rights by ultimately withdrawing the UK from the EU. However, this assumption warrants exploration.

The irrevocability of Article 50 was not raised before the Supreme Court as an issue requiring determination and the Court chose to proceed on the parties’ agreed assumption of irrevocability (see Dr Sanchez-Graells). The failure to raise or address the issue was indisputably politically motivated as opposed to stemming from an absolute consensus on the interpretation of Article 50. If adjudicated, as the domestic court of last resort, the Supreme Court would have been obligated to refer the question of revocability to the ECJ for determination, pursuant to the Article 267 TFEU preliminary reference procedure. The political backlash against the EU judiciary meddling in the manner by which the UK withdrew from the Union would have undoubtedly been immense. Unfortunately, the omission of an Article 267 reference regarding the revocability of Article 50 has not only thwarted the very purpose of the preliminary reference procedure by opening the risk of bifurcation in domestic interpretation, it has also missed an important opportunity to obtain legal certainty.

Article 50’s ‘assumed’ irrevocability is far from uncontentious (Prof Syrpis). While the assumption appears to stem from a strict textual interpretation of Article 50(3), which specifies that ‘The treaties shall cease to apply to the State in question… two years after the notification referred in paragraph 2’ (emphasis added), with only an option for bilateral extension of the period of negotiation provided, compelling counter arguments have been put forward in legal scholarship. Professor Closa, for example, has raised a number of formal and substantive objections to the assumption of Article 50’s irrevocability, the most compelling drawing on a comparative assessment of international law and practice under which a withdrawing state is bestowed a ‘cooling off period’ allowing it to change its decision. Lord Kerr of Kinlochard, the drafter of the Article 50 provision, has also attested to its revocability. Further, Donald Tusk, the President of the European Council, has asserted, in his political capacity, that upon conclusion of the Article 50 negotiation process the status quo could be maintained, meaning that, if the UK was not happy with the agreed terms of Brexit, it could opt to continue to be a member of the EU.

Whether this decision to maintain membership status could be unilaterally reached by the UK as a matter of EU law is of huge constitutional significance at the domestic level. The Miller case deliberated whether the Government could rely on the royal prerogative to trigger Article 50, assuming this will inevitably, and unavoidably, have a direct effect on UK citizens’ rights by ultimately withdrawing the UK from the EU. However, if Article 50 was revocable, and the Government could accordingly issue notice under Article 50(2) without the inevitability of Brexit, the ruling would no longer withstand scrutiny. If the UK was able to issue notice and engage in negotiation with the European Council, put the negotiated terms of the UK’s withdrawal before Parliament for approval, and maintain the status quo if rejected, the Government could rely on its royal prerogative to issue notice under Article 50(2) and go to the negotiation table, with Parliament still able to have a final say on whether the UK ultimately withdrew from the EU on the terms offered. Accordingly, issuing notice under Article 50(2) would not, per se¸ alter any domestic law, and, as such, no Act of Parliament would be required to trigger it.

If we proceed, as the Supreme Court did, on the assumption that notice under Article 50(2) is indeed irrevocable, then the impact of issuing such notice must be explored further. Hypothetically, what if Parliament reached the decision that only partial withdrawal from the EU was desirable; for example, continued access to the single market or ‘soft Brexit’ to use the colloquial term in political discourse. As this will be a matter for negotiation with the European Council, the decision to withdraw on such terms cannot be made prior to notice under Article 50(2) having been issued. Note ought to be made here of the UK’s negligible negotiation power pursuant to Article 50(3). If it does not accept the terms offered, after two years it is stripped of member state status and ousted from the EU with no guarantee of a future relationship of any form. This ‘absolute Brexit’ is the default outcome of activating the Article 50 withdrawal process. In other words, a decision to trigger Article 50 would ultimately be a decision to accept absolute withdrawal if no better option is made available. This is certainly the approach that the Prime Minister sets out in the White Paper presented to Parliament on 2 February 2017, which states at para [12.3] that ‘no deal for the UK is better than a bad deal for the UK’.

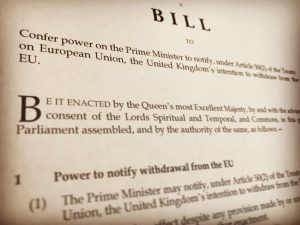

The White Paper provides insight into the Government’s ambitious and arguably unattainable aims in negotiating the UK’s exit from the EU, including controlling immigration while somehow securing the freest trade possible with the EU from outside the Single Market (Prof Peers). Its publication follows the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Bill having passed the first stage of the legislative process by 498 votes to 114 in the House of Commons on 1 February 2017. The Brexit Bill, introduced in response to the Supreme Court’s ruling in Miller, is at present a blank cheque for the Government. At 137 words and comprising just two clauses, it grants the Prime Minister an unconditional mandate to issue notice under Article 50(2), thereby commencing the negotiation process. With the Bill having entered the Committee stage of its journey through Parliament on 6 February 2017, detailed amendments are being debated at present. But to what avail?

One amendment, tabled by the Labour Party, seeks to guarantee that Parliament will have the final say on any Brexit deal reached with the European Council. Proceeding on the assumption that notice under Article 50 is irrevocable, such an amendment will merely serve to permit Parliament a vote on whether no deal is better than a bad deal. Either it will have to accept the Government’s negotiated terms for withdrawal or endure ‘absolute Brexit’ as a default result. It follows that any such amendments to the Brexit Bill will be of no practical effect, for Parliament simply cannot make withdrawal conditional if the Article 50 process is irreversible (see Miglio). Accordingly, in passing the Brexit Bill amended or not, Parliament will have to believe that absolute withdrawal from the EU is in the UK’s best interests as this is the only guaranteed outcome of initiating Article 50.

Legally, Parliament is not obligated to bestow the Government competence to issue notice under Article 50(2). The referendum of 23 June 2016 was not legally binding, despite Parliament’s ability to have drafted it in a way which would have rendered it such. Further, it did not specify what ‘type’ of Brexit was on the ballot. When fulfilling its duty in our parliamentary democracy, acting in the best interests of all citizens and not just in respect of the wishes of those eligible to vote, Parliament must be fully aware that in bestowing the Prime Minister a mandate to trigger Article 50 it is endorsing absolute Brexit as a default result.