By Prof Antonia Layard, Professor of Law (University of Bristol Law School).*

Information about land is valuable, politically, fiscally and – increasingly – as geospatial data products ripe for commercial development. Since William the Conqueror’s Domesday Book was completed in 1086, politicians, campaigners and citizens have wanted to know who owns what. Taxation continues to matter but so does freedom of information. Microeconomics, for example, teaches us that a “free market” relies on symmetry of information: if one party knows more than another, the level playing field is distorted. Money laundering and terrorist financing justify the EU’s pursuit of registers of beneficial ownership. Transparency campaigners argue that open and free data on land ownership is both a citizen’s right and that open registers improve efforts to crack down on tax avoidance. Although rights to privacy continue to resonate in English politics, particularly to beneficial ownership in trusts, the calls for transparency grow louder.

Information about land is valuable, politically, fiscally and – increasingly – as geospatial data products ripe for commercial development. Since William the Conqueror’s Domesday Book was completed in 1086, politicians, campaigners and citizens have wanted to know who owns what. Taxation continues to matter but so does freedom of information. Microeconomics, for example, teaches us that a “free market” relies on symmetry of information: if one party knows more than another, the level playing field is distorted. Money laundering and terrorist financing justify the EU’s pursuit of registers of beneficial ownership. Transparency campaigners argue that open and free data on land ownership is both a citizen’s right and that open registers improve efforts to crack down on tax avoidance. Although rights to privacy continue to resonate in English politics, particularly to beneficial ownership in trusts, the calls for transparency grow louder.

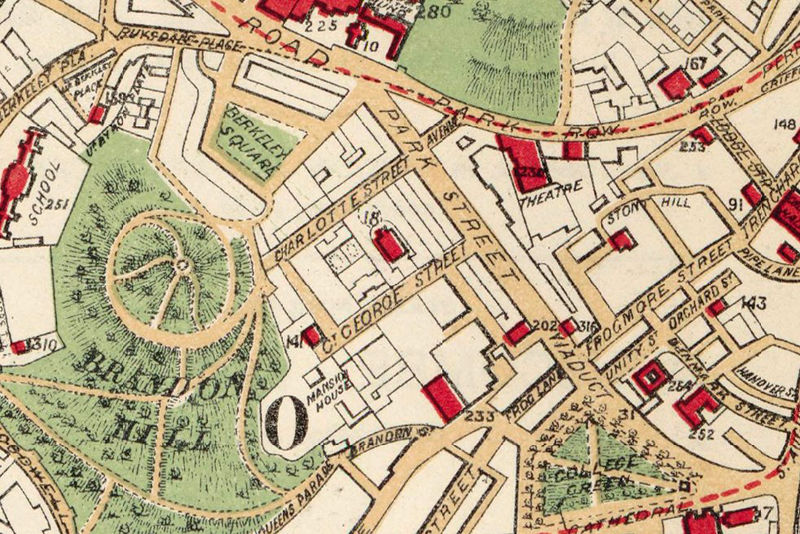

And yet, as these three stories about land secrecy show, we still struggle for information about land ownership and deals. While land registry data is publicly available it is held by estate, rather than being mapped cadastrally, giving a birdseye view of land ownership by presenting the boundaries of land ownership spatially. The paradoxical result, as MSP Andy Wightman has pointed out, is that it is easier to assemble cadastral information for previous generations, based on historical surveys (Domesday, the 1830-1840s Tithe Maps, The Return of Owners of Land from 1873-5 or the 1940s Farm Land Use mapping in England) than map land ownership today. Of course, transparency could be achieved at the stroke of a political pen to find out who owns England (story 1), to understand the extent and range of beneficial ownership of land (story 2) or to avoid the use of “redacting” in “viability assessments” to reduce the amount of newly built affordable housing (story 3). Yet – so far – there is a lack of political will to end ongoing secrecy about land ownership and land deals.

1. Who Owns England?

When Kevin Cahill tried to investigate land ownership in Who Owns Britain (2001), he encountered a wall of privacy. One difficulty was that many acres were not registered with HM Land Registry (before the 2002 Land Registration Act introduced new triggers for registration). Nevertheless, Cahill still found out that (at that time) the Duke of Buccleuch owned 277,000 acres, the Duke of Westminster 140,000, many in central London. Recently investigations, for example by Guy Shrubhole and Anna Powell Smith who run the excellent Who Owns England blog and recently took as their target the South Downs National Park, have found that land ownership in England (as in Scotland) is still highly concentrated. The three great eras of change in land ownership – after the Norman invasion from 1066 onwards, during Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries and grants during the English Civil War and subsequent Restoration – continue to resonate today. As members of the public, however, we do not know “who owns England”. And even if the Government may soon know (they have committed the Land Registry to “aim to achieve” comprehensive land registration by 2030) will anyone else be able to find out?

For even once all land is registered, we have in England and Wales a system that registers estates, rather than the land itself. An estate, a conceptual remnant from feudal times, is commonly understood as a metaphor for time. HM Land Registry keeps registers of freehold and longer leasehold estates and guarantees them, providing legal title by registration (rather than registration of title). Section 58 of the Land Registration Act 2002 confirms that it has always been a fundamental principle of registered conveyancing that registration vests the legal estate in the registered proprietor. Registration does not confirm ownership, it confers ownership, “vesting” the legal estate.

A consequence of the system of estates, useful when land was first being granted in the early days of the Norman Conquest (in the late 1060s and beyond), is that there is no cadastral mapping system of land in England and Wales. While individual estates can be accessed today, searchers will need either the land certificate number or the address and postcode. Applicants will also need to pay for each land certificate searched: £3 for a copy of the land certificate and £3 for a copy of the title plan. Anyone attempting to put together a map of land ownership will be faced not only with an administrative workload, identifying and mapping estates one by one (both freehold and leasehold, which must be requested separately), but also with a significant bill to pay the Land Registry to investigate the estimated 25 million titles showing evidence of ownership.

This steady stream of small sums coupled with the extent of its geospatial data has made the Land Registry hugely valuable. George Osborne (the Conservative Chancellor 2010-2016) made two attempts to privatise most of the Land Registry in 2016 and 2017, proposing the creation of a “NewCo” to develop a market for geospatial data, leaving only a small part of the Land Registry to be held back, including to act as the state guarantor of title. Given HM Land Registry’s then 95% satisfaction rate and reputation as a public body that works efficiently and reliably, privatisation was opposed by articulate and informed critics, notably practicing solicitors. The political appetite for the privatisation dimmed and was particularly quenched by the contribution to the consultation process by the Competitions and Market Authority in 2016. The CMA noted that although Deloitte had valued the Land Registry at £6.2-£7.2 billion for “public information in digital products”, selling all this information as well as the continued ability to continue to accumulate it would confer extraordinary unfair advantage on a single company. Whilst previous monopoly privatisations (of water, for example, or rail) were successful in the 1980s, politically, times have changed (a bit).

For now then, the information on land ownership is to remain in the public sector where it is to be modernised. The Conservatives’ 2017 Election Manifesto promised: “we will combine the relevant parts of HM Land Registry, Ordnance Survey, the Valuation Office Agency, the Hydrographic Office and Geological Survey to create a comprehensive geospatial data body within government, the largest repository of open land data in the world. This new body will set the standards to digitise the planning process and help create the most comprehensive digital map of Britain to date.” One driver for this is to “release more value from the land than is currently being realized” as a lack of transparency about land ownership is perceived to be limiting house building. A side benefit, apparently, is also to improve data for the development of video games.

Prompted by the need to understand land ownership to facilitate increases in housebuilding, the Government also promised in their 2017 White Paper Fixing our Broken Housing Market that contractual arrangements – notably options used in “landbanking” and by intermediary land speculators – will become registrable in new reforms. The political justification for the change is that currently, “local communities are unable to know who stands to benefit fully from a planning permission” and because options could “inhibit competition because SMEs and other new entrants find it harder to acquire land”. Such change would (very usefully) increase the amount of information in relation to each estate but it would do so within the confines of the current system.

Systematic cadastral mapping of land ownership, however, remains off the political agenda. Some freely accessible data available to the technically savvy (polygons) are publicly available thanks to the implementation of the 2007 EU INSPIRE Directive, aimed at producing a European spatial data infrastructure for environmental purposes (and are very helpfully set out by the expert Anna Powell Smith). Of course, with Brexit looming, the status of such information is uncertain (though perhaps it is too late to put that particular rabbit back into the hat). And while the manifesto promised a “a comprehensive geospatial data body within government” we are still waiting to see what will happen in the commitment to introduce “any necessary legislation” … “at the earliest opportunity” … “following consultation”.

2. Beneficial ownership of land

In Seeing Like a State, James C. Scott argued that “legibility”, making people, places and systems visible, has been “a central problem in statecraft” for thousands of years. This is an insight that characterises land ownership as well. Under land registration, some estates and interests are registrable (freehold estates, leases longer than seven years, mortgages, easements, for example), while some (including restrictive covenants or contractual arrangements) remain unregistrable (and so more illegible). Specifically, as all law students learn, the “trust curtain” operates to keep information about beneficial ownership off the land registry. Beneficial interests are illegible to reflect the assumption– in English law and political culture – that trusts are devices that protect the privacy of information, including about land ownership. Of course, many trusts do not aim to benefit from this lack of transparency, it is a byproduct of their construction. Yet secrecy (privacy’s contentious cousin) is clearly beneficial for some.

While beneficial ownership in trusts remains contested, there has been a flourishing of transparency in relation to companies. In 2014, Private Eye uploaded an interactive map of foreign ownership of land ownership, using HM Land Registry information but presenting it cadastrally and free of charge. In 2017, HM Land Registry joined the open data revolution, releasing its information on corporate and foreign corporate landownership. While the information is open data, it remains much less searchable than either the paywalled Land Registry portal or the companies database released by Companies House in 2015, building on its earlier lauded release of company accounts.

Thanks to the EU, this growing legibility for companies is also very slowly being extended to trusts. Complying with the 4th Anti-Money Laundering Directive, the UK has now introduced a Trust Registration Service where the Money Laundering Regulations 2017 have introduced a centralised beneficial ownership register for trusts to provide a single point of access for trustees and their agents to register and update their records online, replacing paper forms as well as increasing (hopefully) searchability. The 2017 Regulations include– for English lawyers – a distinctive articulation of who is a beneficiary. The Regulations require HM Revenue and Customs to maintain the register, giving tax and customs officials the ability to exchange information in the registers with law enforcement and competent authorities. However, these registers are not publicly available. Politically, this restriction was achieved by David Cameron who intervened in 2013 arguing that it was important to balance individual rights to privacy (particularly for family trusts) with transparency. Again, with Brexit looming, trusts may remain more secretive than companies for some time to come (raising particular questions when companies use trust mechanisms to hold their beneficial interests).

This protective treatment for beneficial ownership under trusts is even more striking where assets are held outside of the UK. Offshore trusts make use of the split between legal and beneficial ownership by separating jurisdictions along these lines. Legal ownership and the registration of the trust are conventionally in low tax jurisdictions (for example, the British Virgin Isles and the Bahamas) where they attract minimal liability. While distributions made to beneficiaries in the UK will attract a tax liability, there are tax advantages that underpin how these vehicles are structured. For example, inheritance tax is not payable on the assets as the trust can run – often for generations – investing and increasing assets. Now, after a sustained campaign by advocacy organisations and bipartisan political interventions, British Overseas Territories will be required to maintain public registers for those trusts that own property in the UK by 2020 (or have them imposed on them). Bristling at this extra-territorial intervention, representatives of Bermuda, the Bahamas and the British Virgin Isles have claimed that the proposed rules represent new instances of colonialism.

While trusts lag behind companies, and the separation of legal and beneficial ownership remains a viable device to achieve secrecy, international political pressure (particularly in light of the Panama Papers) means that beneficial ownership is slowly, slowly, becoming more legible for law enforcement purposes. For members of the public, however, beneficial interests in land remain hidden behind the trust curtain, they are missing on the land certificate. The balance between transparency and the right to privacy remains tilted towards secrecy.

3. Commercial confidentiality in affordable housing

Secrecy is also evident in land deals, with particular effects for transparency in respect to affordable housing. England has a widely acknowledged housing crisis, or more specifically, an affordable housing crisis. With around 85% of all new housing built by private developers, much of recent affordable housing provision (if we are relaxed about what “affordable” in this context actually means) has come from the private sector. The 1947 Town and Country Planning Act brought in a system, quite distinct from zoning, that nationalised development rights for landowners. Initially, development rights could be granted in return for betterment payments (which have had a decidedly checkered history) but today planning permission is granted for development subject to fixed community infrastructure levies (CIL) and possibly also planning obligations (s106 agreements) including for affordable housing.

Since 2012, and the introduction of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), affordable housing need only be included in new developments if it is financially “viable” to do so (para 173). Viability is, these days, a proxy for profitable although in previous formulations “viable” was used as a synonym for “achievable”, not necessarily quantified in financial terms. Viability has also been highly profitable for consultants, who work for both developers and, sometimes, local authorities, producing spreadsheets tallying the costs and concluding that affordable housing is, or is not, viable. Many times the spreadsheet says “no” to the provision of affordable housing, even as part of a development of luxury flats.

The expertise at the heart of viability assessments is not the calculation (often this is a rather straightforward matter of adding and subtracting within a spreadsheet). The expertise lies in the estimation and identification of costs, valuation of land and negotiating what a reasonable profit margin might be. The most contentious input is often the cost of the land, with developers and landowners keen to use “alternative use values” (AUV), incorporating “hope values” for the site. In contrast, concerned local authorities, notably the Greater London Authority in their 2017 Suplementary Planning Guidance on Affordable Housing, are moving to requiring the use of “existing use value +” (EUV+) as the land value input. Valuation, it is often said, is an art, not a science and the role of land agents in price setting (particularly in rural areas) remains poorly understood. While the price paid for the land will eventually become public knowledge, being recorded by the Land Registry and available freely online in valuation websites linked to estate agents, during this crucial negotiation phase, land prices are rarely publicly available.

When viability assessments – which do contain these costs – are released, they are often redacted, with black boxes inserted into assessments blocking out sight of the figures beneath. Land costs, development costs and projected profit can all be hidden in this way. The justification for this practice is that these figures are commercially confidential. Viability assessments are generally not required to be publicly available, in contrast, to the other reports and documents often submitted as part of the planning process (highways, flood risk or noise assessments). Occasionally, campaigners get a lucky break, “unredacting” assessments through conventional word processing techniques, illustrating the calculations for individual projects, including anticipated profit and land values.

While central Government has indicated in its proposals to reform the NPPF that viability assessments may be required to be open to greater scrutiny, we are still uncertain whether this will happen. The impetus for change has come from local authorities, particularly in London, notably Islington and Greenwich. In 2017 the Greater London Authority, Affordable Housing and Viability Supplementary Planning Guidance stated that the presumption in London will for now on be that viability information is publicly available and that if commercial confidentiality is to be claimed as a reason for secrecy, then the Local Planning Authority or the Mayor “would need to be convinced that the public interest in maintaining the exception outweighs the public interest in disclosing the information. Other local authorities may follow suit. In November 2017 Bristol City Council also announced that viability statements should be publicly available as part of a broader – and distinctive – approach to affordable housebuilding.

Transparency about affordable housing deals is contentious because we see a clash of public and private numbers. Public numbers conventionally populate a planning process, they include local authority housing numbers, details from noise, flood or highway assessments as well as details on consultations. Private numbers are figures claimed to be “commercially confidential” as they concern costs incurred by private sector developers including for construction, borrowing or the price of land. Broadly, the courts have been resistant to the call for transparency, insisting on the importance of commercial confidentiality in large development projects. In R. (on the application of Perry) v Hackney LBC [2014] EWHC 3499 (Admin), for example, Paterson J. rejected any claim that local councillors acted illegally by not consulting the viability information directly and by not requiring it to be made publicly available.

There is also as Estelle Dehon notes, even a practice of “double confidentiality” in some places. “Local authorities take the view that viability assessments are so commercially confidential that they should not ordinarily be provided to Councillors, but instead sent to independent property consultants or chartered surveyors, who evaluate them on a confidential basis …. Councillors and the public are given only headline versions of this evidence in officer reports”. This is a matter of practice, with no legal requirement either to keep such assessments private or make them public but cultural practices are often deeply embedded.

Rather than relying on judicial review remedies to compel publication by local authorities, the First Tier Tribunal of the Information Commissioner has taken a different tack. Since claims can be brought to the Information Commissioner under the English implementation of the 2004 Environmental Information Regulations (implementing Council Directive 2003/4/EC on public access to environmental information, implementing the 1998 Aarhus Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters), this provides an opportunity of making a citizen’s rights to information a starting point. As a result, Information Commissioners have been able to ask broader questions than whether a claim in judicial review should be upheld against the local authority, investigating instead, whether citizens have a right to see these calculations. They have found for campaigners, making information publicly available in key disputes (Royal Borough of Greenwich vs ICO & Shane Brownie EA/2014/012 and RB and Clyne vs ICO & Lambeth EA/2016/0012). As well as releasing information for these particular claimants this trend started to change the discourse on commercial confidentiality.

The secrecy embedded in these land deals is premised upon a debate about the characterisation of the information. If viability calculations are planning documents, they would conventionally be transparent. If viability calculations are part of developers’ documents, they would conventionally be commercially confidential. The difference, in part, depends on the location and identity of the questioner, a concerned citizen, a local authority planning officer or a private developer or planning consultant, will take very different views of which category this information fall into. Donna Haraway famously rejected the “god-trick” of seeing everything from nowhere” and in planning and land deals different actors take different approaches. Nevertheless, planning is only permitted if a planning authority gives permission, development rights were nationalised by the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947. The ability to develop is then no longer automatically part of land ownership. For this reason, there are good grounds to argue that viability assessments should be public, as they are used to justify not delivering on the affordable housing commitments set out in local authority planning policies (often long before the price for the land has been paid). As long as viability assessments are not publicly released then, these are, to use Nik Rose’s 1971 words, “undemocratic numbers” doing secretive – and highly ideological – work.

4. Conclusion

Information on land ownership is valuable. In the context of the proposed Land Registry privatisation, the Competition and Markets Authority went as far as to say information was so valuable that selling it to a single company would be anti-competitive. Conversely, secrecy is also valuable, whether to reduce tax liabilities or to maintain privacy by using trusts, for example. In James C. Scott’s later (2010) book The Art of Not Being Governed, he builds on ideas of legibility to consider the people of the Zomia who choose to live outside the reach of the state, making a deliberate choice to move into the hills as an act of state avoidance. Similar moves are possible for English landownership, moving into trusts, perhaps geographically offshore, or hiding behind “confidential” viability calculations. Land ownership details and land deal information could all be publicly available, we live in an age of “big data”. For now, however, we wait.

* Note: This blog is based on a plenary talk given at the 2018 Association of Law, Property & Society at the University of Maastricht. It was a counterpart to a very vibrant talk on Privacy, Property, Politics, and Polarization given by dr. Anna Berlee, LL.M., Molengraaff Institute for Private Law Utrecht University (whose 2018 book Access to Personal Data in Public Land Registers: Balancing publicity of property rights with the rights to privacy and data protection will soon be added to the University of Bristol Law School Library). I would like to thank the ALPS Executive for giving me the opportunity to talk to property colleagues from around the world about land secrecy in England. A longer version of the third story on viability will soon be published as a contribution to an edited collection by Mike Raco and Federico Savini in Planning and Knowledge: How New Forms of Technocracy are Shaping Contemporary Cities.

The positive feedback between land pricing and planning assessments reducing the proportion of ‘affordable’ housing or breaching recommendations on density of occupation (e.g. room size, number of stories) seems worth remarking.

Developers can anticipate waivers as a result of high bids and payments for land skewing the profitability estimates/rhetoric anticipating that the Local Authority will give way on this rationale, increasing precedent and spiralling up land prices leading to the reduction in quality explained in NEF’s ‘Rethinking the Economics of Land & Housing’ e.g p98.

‘Developers’ control of strategic land (i.e. no planning permission yet) via the use of options agreements, which are private contracts with landowners .. and are generally not publicly disclosed’ (p97, paraphrased) contributes to the price inflation enabled by secrecy.

Apologies for not responding sooner, I hadn’t seen your reply. You are of course absolutely right and NEF’s work on this is exemplary. Landowners have been told over and again that they should only pay for “policy compliant” land. The role of third parties here is fascinating but (as far as I know, largely anecdotal). Will Oliver Letwin’s review make any difference?